\”Everything works somewhere; nothing works everywhere,\” writes Dylan Wiliam in his book Creating the Schools Our Children Need. To that particular I would add, everything works at something; nothing works at everything.

Together, the two maxims describe what my research team found whenever we evaluated the Louisiana Scholarship Program, a statewide school-voucher initiative: this program satisfied some of its goals but fell well short of others, including those of raising student scores on state tests. Below is really a cautionary tale about good intentions and seemingly reasonable decisions leading to unintended consequences.

Student performance on standardized tests in Louisiana has trailed national averages for decades. In the 2021 8th-grade reading results on the National Assessment of Educational Progress, Louisiana public schools tied for 42nd in america and rated significantly greater than just one jurisdiction, the District of Columbia. Only 25 percent of Louisiana 8th graders scored as proficient or above in reading, similar to the 23 percent rate in 2021 but higher than the abysmal 17 percent rate in 1998. NAEP reading scores for Louisiana 4th and 12th graders have been similarly disappointing, as get their math and science scores.

The private-school sector within the Pelican State is comparatively large, for 3 likely reasons: the traditionally low academic performance of the state's public schools; Louisiana's French-Catholic heritage, which has boosted many parochial schools; and the state's troubled history of racial segregation. In 2011 -12, when this story begins, Louisiana had 394 private schools enrolling 112,645 K -12 students, or nearly 16 percent of Louisiana K -12 students, well above the national private-school average of 11 percent. The private-school sector in Louisiana is really a diverse mixture of religious and secular schools, with Catholic and evangelical Christian schools dominating the scene. Annual tuition rates in 2021 ranged from $2,000 to $19,660, with a school-level average of approximately $6,000.

In 2005, Hurricane Katrina raged in, devastating the city of recent Orleans and environs. The flood damage to a lot more than 300 public schools was so extreme they'd to become condemned. Because the storm left many area private schools intact, the Catholic Archdiocese of recent Orleans, waiving tuition, initially absorbed a large number of students whose public schools have been ruined. Many months later, after Hurricane Rita ravaged areas of the Houston area, the us government established hurricane vouchers for the two storm-damaged regions, temporarily covering the private-school tuitions of educationally displaced children.

In the wake of Katrina, Louisiana lawmakers established two major private-school choice programs. The first was the Elementary and School Tuition Deduction policy, enacted in 2008. This initiative allows families to deduct on their state income-tax return up to $5,000 per child in private-school educational expenses. The groups of a lot more than 106,000 from the 112,000 students attending Louisiana private schools in 2012 claimed the deduction. The second program was a student Scholarships for Educational Excellence Program, which in '09 began providing private-school vouchers to 624 low-income students within the parishes of Orleans and nearby Jefferson. This program served as a pilot for that larger, statewide Louisiana Scholarship Program, launched this year.

State policymakers also dramatically refashioned the public-school system in New Orleans. Gone were residential attendance zones, the teacher collective-bargaining agreement, and almost all of the public schools the Orleans Parish School Board directly operated. Within their place arose a brand new kind of urban public school system, dubbed the Recovery School District. Overseen by state education officials, the new district was composed almost entirely of public charter schools that would be held accountable for student achievement on state tests. Douglas Harris at Tulane University figured this package of market-based reforms-expanded school choice coupled with results-based accountability-substantially improved the test scores of students attending the city's public schools (see \”Good News for brand new Orleans,\” features, Fall 2021).

The pilot voucher program had 1,950 students enrolled in 2012 when it expanded statewide and have become the Louisiana Scholarship Program. Demand for the program was strong from the start: a total of 9,736 students applied that first year, with 5,296 receiving vouchers and 4,944 with them to attend a private school. It is primarily the 2012 -13 applicant cohort, a majority of whom lived outside New Orleans, that people evaluated during the period of four years. This program enrolled 6,695 students in 2021 -17, a small amount of 9 percent from its enrollment peak of 7,362 in 2021 -15 (see Figure 1).

Participation within the voucher program is fixed to low-income students in low-performing public schools. To qualify, the wages of the child's family must be at or below 250 percent of the federal poverty line, which in 2021 -17 was $60,750 for a group of four. Applicants also must either be entering kindergarten or be attending a public school graded C, D, or F by the state's test score-driven school accountability system. About 1 / 3 of the K -12 students in Louisiana, or nearly 250,000, were entitled to the scholarship program in 2012, when 4 % of the eligible student population applied to the program. Nearly 90 percent from the eligible applicants were Black and also over 80 % were entering grades 1 -6 that year.

Applicants win spots in the program by means of a government-run lottery, and the students who did not win the lottery provided the control group for the study. Students in D or F schools receive priority in this lottery, so few students from C schools have obtained scholarships. Students with disabilities also receive priority, because they are placed automatically within their private school of choice if your seat can be obtained. The lottery simultaneously awards students with scholarships and placement in a specific private school, drawing from the school preferences listed by parents. Unlike most private-school choice programs, the scholarship award takes place following the school-shopping process, not before it.

The voucher value is limited to 90 % of the local and state per-pupil funding inside a student's school district or even the tuition rate the student's chosen private school charges, whichever is less. Annual tuition at participating private schools ranges from $2,966 to $8,999, with an average of $5,437, compared to average state and local per-pupil funding of $8,500 in Louisiana's public schools this year -11.

Why might a private school decide to not have fun playing the Louisiana Scholarship Program? One good reason might be that participating schools must undergo regulations regarding financial practices, curriculum, student enrollment, mobility, safety, and achievement. They have to provide financial audits to convey officials each year and keep a curriculum the state Department of Education judges to be of equal or higher quality towards the curriculum in public places schools. Participating schools cannot select their voucher students and must instead admit them solely through the placement lottery administered by the state.

All participating private schools must administer the state's accountability tests annually to voucher students in grades 3 -8 and again in grade 10. Participating schools with at least 10 voucher students per grade are assigned school-performance ratings based on voucher-student scores on the state test.

As within the test-based accountability model put on public charter schools in Louisiana, the state can sanction private schools taking part in the voucher program. Any of three conditions leads to state sanctions. First, a school is sanctioned when the average rate of gain of voucher students around the state test is so low that the school qualifies to have an F grade. Second, a school is sanctioned if less than 25 percent of its voucher students score at or above their state benchmark for proficiency. Finally, participating schools are sanctioned if their annual financial audit reveals improprieties or raises concerns concerning the school's future viability.

A private school that receives a sanction is prohibited from enrolling new voucher students until it remedies the condition that led to the penalty. By 2021 -16, the final year of information collection for the study, 35 of the 122 private schools within the program had been sanctioned for at least twelve months.

These regulations on admissions, testing, and curriculum render the Louisiana Scholarship Program probably the most highly regulated among the 58 private-school choice programs in the united states. Why put so many restrictions on the private-school choices available to parents?

The background and context of education in Louisiana likely led policymakers to opt for such a highly regulated model. The Pelican State continues to have many racially stratified schools. The majority of the D and F public schools within the state serve a big part low-income student population. Thus, restricting the voucher program to students from low-income families attending failing schools, and requiring the colleges to forgo any admissions standards, was expected to prevent the program from worsening school-level racial and income segregation.

The private schools in Louisiana ranged dramatically in tuition rates, which likely serve as a rough proxy for school quality. Officials anticipated that, out of the box common in voucher initiatives, few of the higher-tuition private schools would elect to participate in the program, since they would have to foot most of the price of educating voucher students. Moreover, their state Elementary and Secondary School Tuition Deduction policy provided the fee-paying customers of private schools having a significant cost rebate that didn't require school to take on any extra state regulations or paperwork, lowering the incentive for schools to join the voucher program and accept its regulatory requirements.

Policymakers expected the lower-quality, under-enrolled private schools in Louisiana to register to sign up within the voucher program, so they developed a results-based accountability system that would remove schools from the program when they produced low student test scores. An identical regulatory system seemed to be working well for the public charter-school sector in New Orleans. Mandating that private schools administer the state accountability test allows an apples-to-apples comparison of faculty performance. It all seemed so sensible at that time.

Fewer than a third from the private schools operating in Louisiana this year agreed to have fun playing the Louisiana Scholarship Program. That was the smallest share of faculties to participate in a statewide, means-tested private-school choice program of all such programs in the country, and that we sought to know why. Brian Kisida, Evan Rhinesmith, and that i implemented market research of Louisiana private-school leaders that revealed the very best factors deterring private schools from joining the voucher program. We discovered that these leaders feared more regulations might arise in the future and hamper their independence or threaten their religious identity. Additionally they concerned about the integrity of their admissions policies, plus they didn't such as the pressure to adhere to the state's curriculum standards.

Evidence from a survey experiment conducted in other states suggests that the kinds of regulations in place in Louisiana may discourage private schools from taking part in choice programs. Corey DeAngelis, Lindsey Burke, and I sent brief email surveys to every private-school leader in Florida, California, and Ny, asking when they would be likely to take part in a private-school choice program offering a $6,000 voucher. Survey takers were randomly split into five groups. Those in the very first group were asked about their willingness to participate within the hypothetical program with \”no strings attached.\” Those in the other four groups were inquired about participating under a specific regulatory requirement.

One third of private-school leaders who have been told they'd face no additional regulations said these were \”certain\” they'd take part in this type of voucher program. Among school leaders who were told the hypothetical program would mandate an open-admissions policy, just 14 percent said they would be certain to participate. Of those who were told that they could be necessary to administer their state accountability test to all voucher students (with the results reported publicly), 24 percent said they'd be sure to participate. The rest of the two conditions had no important effect on leaders' expressed willingness to sign up: a requirement the school administer a norm-referenced test of their choosing; and a mandate the school accept the voucher because the full cost of educating the kid.

What types of private schools did participate in the Louisiana Scholarship Program? When compared with non-participants, participating schools were more prone to be Catholic, have lower enrollments, and have student populations which were disproportionately made up of racial or ethnic minorities. The typical participating private school was familiar with serving socially disadvantaged students willing and able to increase its enrollment. Surprisingly, average tuition levels were not a significant factor in separating participating schools from non-participating ones in Louisiana.

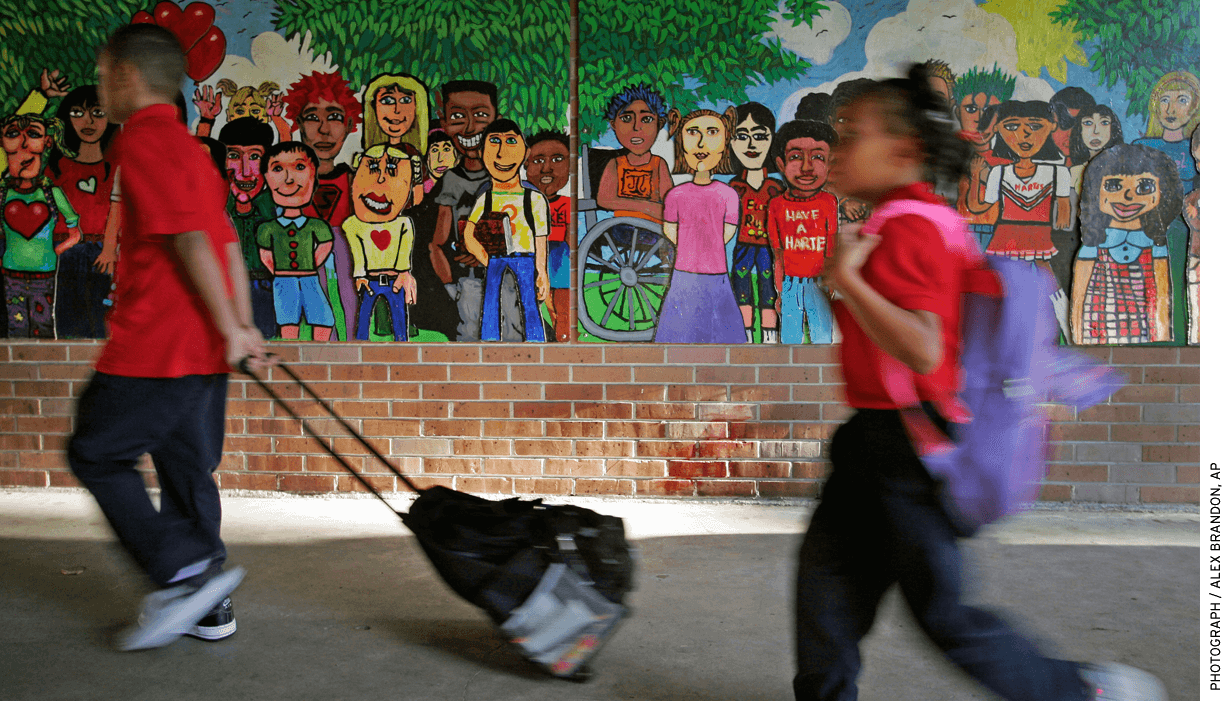

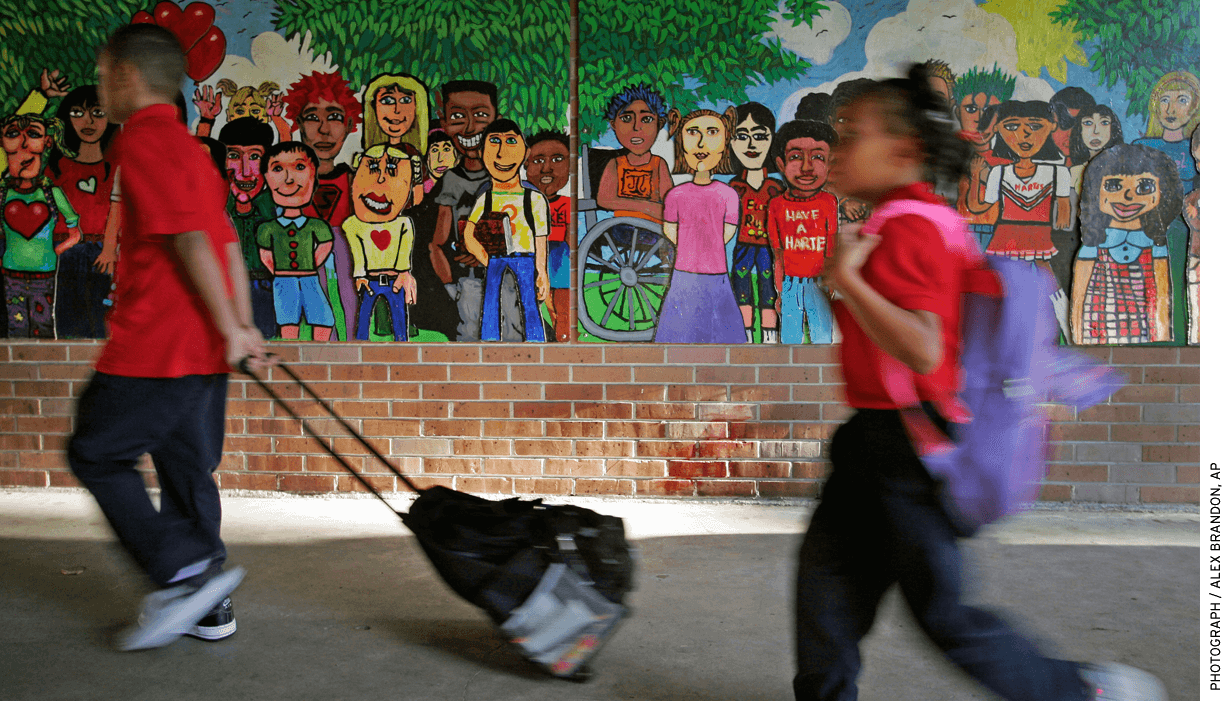

The scholarship program was designed to serve a very disadvantaged population: kids from low-income families who have been attending a public school that produced consistently low test scores.

It is therefore no surprise that Yujie Sude and I found almost no evidence that the voucher program \”cream-skimmed\” easy-to-educate students. At the application stage, the program attracted a highly disadvantaged population of scholars. Louisiana public-school students were more likely to affect the voucher program if they were low income, African American or Hispanic, minimizing test performers. Students in the earlier K -12 grades were much more likely to use than older students, suggesting that parents tend to be more willing to switch the youngster from a public school to a private one when they are younger and perhaps able to better adapt to their new school environment.

Which students stayed in the program? Several factors were associated with persistent voucher use over three consecutive years. Students with lower initial test scores were more likely to persist than were students with higher scores. Girls and students who enrolled initially in earlier grades were more likely to continue than boys or students who were only available in later grades. Students in private schools which had lower minority enrollments which were located a shorter distance from home were also more prone to persist, as were students surviving in public-school districts that had lower per-pupil spending.

After many of these factors competed, how select was the voucher-student population 3 years after application? Characteristics related to student disadvantage tended to differentiate three-year voucher users from students who never applied to the program. Compared to those who didn't apply, students who participated and continued for three years were more likely to be female, low income, and African American. The Louisiana Scholarship Program did flourish in expanding school choice to a relatively disadvantaged population of scholars.

Many commentators declare that parental choice programs worsen segregation. To check that claim, Jonathan Mills and Anna Egalite analyzed the result that initial voucher users had around the degree of racial integration in both the general public schools they left and the private schools they joined (see \”The Louisiana Scholarship Program,\” features, Winter 2021). First, they established a benchmark for racial balance in every school, pegged towards the racial composition from the local community. They determined whether each student who used in a private school this year underneath the voucher program had an integrating or segregating effect. For that public school the student was leaving, the student was deemed to have had an integrating effect when the race of the student was overrepresented at that school, because of the community benchmark. But a transferring-out student were built with a segregating impact on that school when the student's race was under-represented there. Conversely, a transfer right into a private school better integrated it if the student's race was under-represented and additional segregated it if the student's race was overrepresented.

The researchers found that 83 percent of initial student transfers underneath the program had an integrating impact on the racial composition of the public schools they left. Within the private schools they joined, about half of the students generated better integration and also the other half lessened integration. Even just in the 34 Louisiana public-school districts still within order from the court to integrate by race, 74 percent of the transfers underneath the voucher program brought the general public schools closer to the aim of racial integration. Thus, this program has operated like a voluntary school desegregation program, although the racial integration of public schools wasn't its primary purpose.

The main purpose from the scholarship program ended up being to improve academic outcomes. With that goal, it clearly fell short. Using gold standard experimental methods, Jonathan Mills and I determined the results of this program on student scores on the state accountability test tended to be negative, especially in math, so long as four years after initial scholarship use.

For the scholars who took part in the voucher lotteries and for whom we had both baseline (2011 -12) and subsequent test scores, the results of the scholarship program on achievement varied between negative and neutral (see Figure 2). At baseline, the math test performance of the lottery winners was statistically equal to those of the control-group students (that is, those who didn't win a voucher placement). But effects around the math performance from the scholarship students were negative and enormous within the newbie of the program, when students were adapting to their new schools and, likewise, the colleges were adjusting to them. The voucher students recovered some of their lost ground around the state math test the second year and delivered math scores which were statistically similar to the control group in year three, once the state switched to a different accountability test and neither public nor private schools were attributed for the results. In year four, when test-based accountability was reestablished statewide, the voucher program again produced negative impacts on math scores; these were moderately large.

The reading test-score impacts from the program followed a trend like the math scores however with consistently smaller effects, many of which weren't significantly different from zero. For those students for whom we had baseline test scores, the reading impacts of the program were negative and moderately large the very first year, and much smaller and not statistically significant in the second, third, and fourth years.

The achievement impacts from the scholarship program were not uniform for those groups of students. Within the fourth year, the side effects of the program on test scores were less than half as large for Black students in terms of non-African American students. Also, voucher students in grades 4 and 8 took the primary state accountability test, while those who work in grades 3, 5, 6, and seven took a form of the test that was scored on a different scale. For that latter group, the negative test-score results of the program were less than half as large as for those who took the main state test.

The results of the voucher program on student test scores also varied according to key features of the college the student most preferred. Matthew Lee, Jonathan Mills, and I determined the achievement effects of this program were much less negative, and in some rare cases even positive, for subgroups of students whose preferred private schools ranked in the top 1 / 3 of participating schools regarding higher tuition, higher total K -12 enrollment, or perhaps a greater number of instructional hours for students.

Educational attainment-how much schooling a person ultimately completes-greatly influences his or her later life outcomes, and researchers have increasingly turned to studying the impacts of education programs on student rates of high-school graduation and college enrollment, persistence, and completion. Not enough students within our experimental sample were of sufficient age to have graduated from college for all of us to look at that important outcome. However, more than 1,000 students who took part in the voucher program's lotteries completed high school and could have enrolled in college. Did the negative test-score results of this program decrease their rates of school going?

Heidi Holmes Erickson, Jonathan Mills, and that i discovered that the Louisiana Scholarship Program didn't have impact on college entrance for college students. After senior high school, voucher users enrolled in a two-year or four-year college for a price of 60.0 percent, which was equivalent to the 59.5 percent enrollment rate of the control group.

Opponents of private-school choice may use the results in our study to argue that \”free market\” approaches to education have failed. However, the initiative that we evaluated was clearly not really a pure free-market education reform. Free markets generally require: 1) that new suppliers can easily enter the market; 2) that prices can vary across providers and various versions of the service; and three) that customers are the main judge from the quality of the service. None of those conditions held for that Louisiana Scholarship Program. New suppliers were virtually prohibited from emerging, as private schools needed to operate for two years with only fee-paying customers before these were permitted to participate. The price of the service was largely fixed through the voucher formula, and fogeys were prohibited from paying more for any higher-quality education, a minimum of within the program. A government-run lottery placed each voucher student inside a school, and government overseers determined which schools could and could not still enroll new voucher students. Even though parents were able to communicate their preferences about school placement, it had been the state, not the parents, who made the final selection.

School choice programs often aim to reduce racial segregation in schools. The Louisiana Scholarship Program succeeded by doing this. Things are good at something. The statewide launch of the enter in 2012 better integrated Louisiana's public schools, as most voucher-program participants left public schools by which their very own race was overrepresented. Persistent scholarship users were more prone to be Black and to have had lower initial test scores compared to those who didn't apply to this program. Furthermore, the program saves the state money, because the voucher more less than $6,000 is just about sixty-six per cent of the combined local and state per-pupil funding in Louisiana's public schools.

The regulatory framework from the program rested on several ideas: that private schools accepting government vouchers are comparable to public charter schools; that low-performing schools will improve with government incentives to do this or be kicked from the program; and that student test scores are the most useful single measure of school performance. All of these notions are subject to question.

Private schools vary from public charter schools in 2 critical ways in which affect how they may be effectively regulated. First, private schools have a choice in whether or not to take part in voucher programs, accepting government funding and the regulations that include it. In Louisiana, where tax policies indirectly subsidize families who pay tuition out of pocket, private schools have plenty of paying customers and thus greater latitude to turn on the chance to serve disadvantaged students on state scholarships when the offers are not appealing to them. Public charter schools don't have any such choice, as the government is the only reliable funding source.

There is little evidence that education overseers can help schools overcome using regulatory carrots and sticks. Student test-score performance is really a product of many complex factors, including family background (see \”How Family Background Influences Student Achievement,\” features, Spring 2021), school culture, teacher quality, child nutrition, test preparation, and curricular alignment using the test. Actual levels of student learning are in there somewhere, but it is a crowded room of factors that many private schools with established educational programs and cultures cannot change over the course of a couple of years, even if a regulatory system incentivizes them to achieve this. The evaluation literature on aggressive efforts at systematic school turnaround reinforces this time: school improvement is a slow, difficult, evolutionary process.

Removing private schools in the program when they neglect to boost student test scores might seem as an automatic method for improving outcomes by \”chopping off the lower tail of the performance distribution,\” but where do the affected students go instead? If the existing private schools are already full and brand new ones are prohibited from serving voucher students during a long probationary period, their state sanctioning system merely serves to limit the academic options of oldsters and students.

Finally, student scores and annual gains on the state-mandated accountability test are only one way of measuring school performance. They capture only a part of what we should would consider actual student learning, and advancing student learning is only one of numerous goals of publicly financed education. We charge schools with instilling civic values in students and developing positive character traits of persistence, conscientiousness, and respect for other people and the norms of society. When Thomas Stewart and that i polled an area of 40 parents participating in the D.C. Opportunity Scholarship Program how they assess the academic progress of their child in school, none of them selected \”standardized test scores\” as the metric. Instead, they said they used \”student motivation to understand,\” \”student grades,\” \”positive student attitudes toward school,\” and \”positive student behaviors toward schools\” as measures of whether their child was succeeding. The private schools taking part in the Louisiana Scholarship Program might be delivering these more nuanced but vital outcomes for their voucher students, but determining that will require a more comprehensive assessment of faculty performance.

In order to accomplish anything, schools must keep their students safe. Recent surveys claim that school safety now rivals academic concerns because the major reason parents seek private-school choice. Public regulators would be wise to work indicators of school safety as well as an orderly school environment to their measures of whether a college is performing in a satisfactory level.

The Louisiana Scholarship Program didn't flourish in raising student scores on the state accountability test. Actually, it had a clear negative impact on math scores along with a possible, though less severe, negative impact on reading scores. Nothing is proficient at everything. Our evidence suggests that about 50 % of the negative test-score effect is probably because of public schools more carefully aligning their curriculum to the tested material and systematically implementing techniques for preparing students for the test. Still, it's clear that the program did not positively affect scores around the state test. Insofar as state accountability test scores are used because the litmus test for effectiveness, the Louisiana voucher program did not allow the happy times roll down within the Bayou.