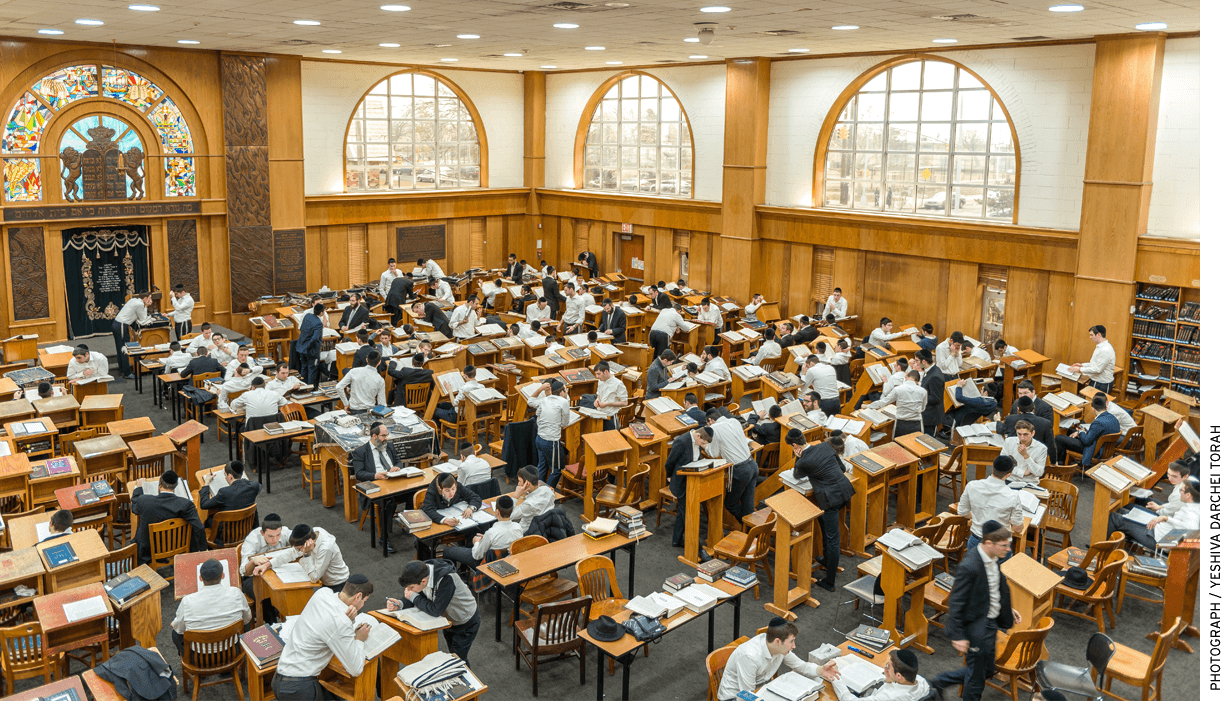

When the New York Times ran an article headlined \”Do Children Obtain a Subpar Education in Yeshivas? New York Says It Will Serve them with Out,\” the newspaper illustrated the piece with a photo of a Jewish school in Queens.

An administrator from that school promptly complained to the Times about its photo selection, mentioning that six from the school's recent graduates had attended Harvard School.

So the Times website exchanged the photo, replacing it and among a Jewish school in Brooklyn. An administrator there complained too-noting that the school offers 24 Advanced Placement courses, including ones in physics, information technology, and calculus.

The Times then took down this second photo, replacing it online with a picture of the advocate whose organization sued the governor of recent York so that they can force more secular instruction in Jewish private religious schools.

This episode from December 2021 neatly reflects the years-long policy battle within the curricula in Jewish schools in Ny and the government's role in overseeing them. High-quality educational offerings and outcomes are met with accusations of inferiority. And the Times is paying close, if clumsy, attention.

One can realise why. It is a good story, of great interest well beyond the Jewish community. Jewish schools educated more than 151,000 students in Ny State in 2021, the last year a careful count was done. That's a lot more than the number signed up for the Philadelphia City or North park Unified public-school districts. And taxpayers possess a stake in how well the yeshivas are doing their jobs. The Jewish schools absorb a lot more than $100 million annually in city government funds for things such as textbooks, special education, security, and transportation. What's more, if yeshiva students don't get the abilities essential to participate in the economy, other taxpayers may be stuck supporting all of them with subsidized housing and health care, the schools' critics contend.

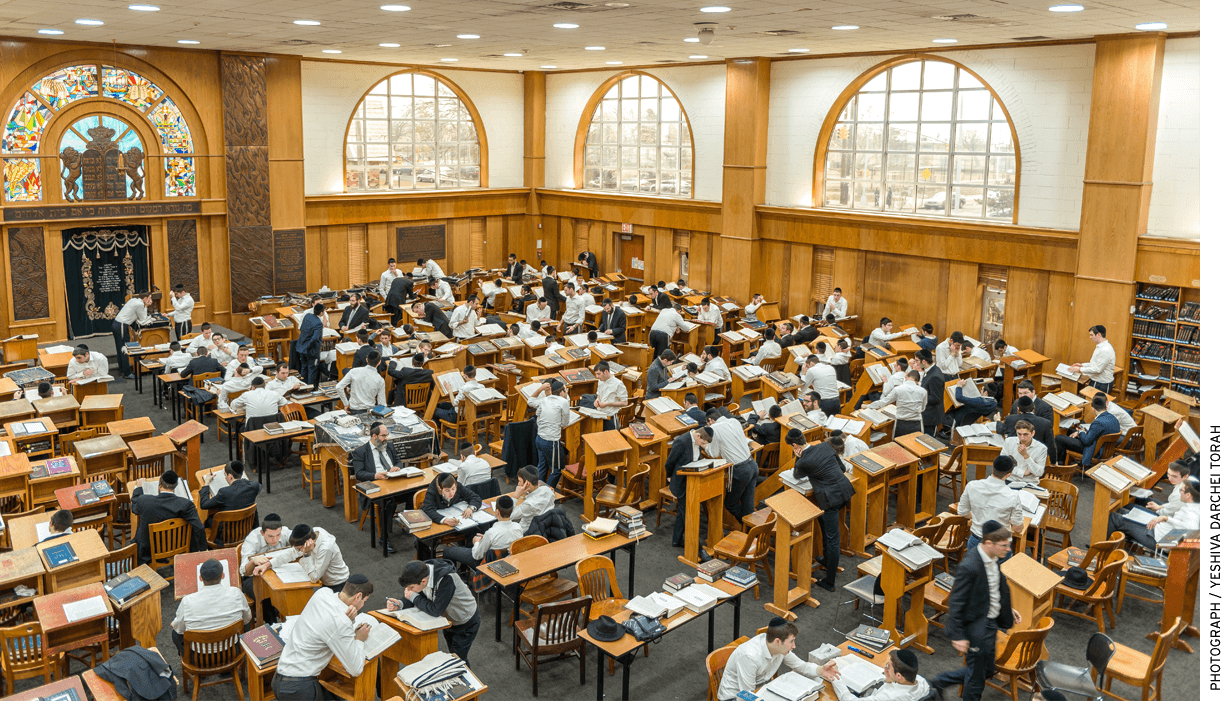

Some Jewish schools serve essentially like other private schools, as feeders to secular higher education or the workplace. The critics, though, are centered on the education in ultra-Orthodox schools, especially Hasidic institutions. Hasidim are Orthodox Jews loyal to a particular charismatic rabbi; they live in tight-knit communities, dress yourself in traditional garb, and closely stick to the teachings from the Torah and Talmud. Boys spend many of their school day studying these sacred texts and related writings, often to the near exclusion-critics contend-of traditional school subjects for example English and math.

The mayor of New York, its city schools chancellor, the state and federal courts, as well as Governor Andrew Cuomo have been drawn into the dispute, which at some point was used by a state senator to hold up negotiations over the Empire State's entire $168 billion annual budget.

It's also a story that extends beyond education outcomes and Ny politics to deeper philosophical and legal issues: religious liberty, state power, and family freedom. How much authority if the city and state have to impose the government's vision of the education on a religious minority that would prefer to be left alone? How much power should parents have to send their kids to varsities that emphasize religious subjects at the expense of topics for example science or math? Does society have a responsibility to make sure that all children get an education that allows these to participate in democracy and the workplace? And who determines the solutions to these questions-parents, politicians, courts, bureaucrats, advocacy groups, or some complicated combination thereof?

The advocate whose photo the Times finally settled upon, Naftuli Moster, was dissatisfied with the education he received in the yeshivas he attended growing up. Inside a federal civil complaint his advocacy group filed in 2021 against Cuomo and also the state commissioner of education, he cited a New York Post headline contending \”Jewish schools are dooming young men to poverty.\” The complaint-which in January 2021 was dismissed in district court for insufficient standing-charged that \”although non-public schools are needed by state law to provide a substantially equivalent secular education, very little secular education is provided for the most part Hasidic ultra-Orthodox Jewish non-public schools. . . . The word what of instruction is nearly exclusively Yiddish, exactly the same language the scholars speak at home, and often includes some Hebrew and/or Aramaic texts.\”

Then in March 2021, a Jewish advocacy group that props up religious schools, Parents for Educational and Religious Liberty in Schools, along with five from the schools plus some individual parents, filed a lawsuit in state court. That fit challenged guidelines the state of Ny announced late last year, which had required onsite evaluation of all non-public schools every five years. Schools that failed those evaluations risked losing public funding for textbooks and transportation, and fogeys at failing schools potentially faced liability under truancy laws.

The complaint contends the guidelines \”violate both Usa Constitution and also the Ny Constitution,\” invoking the disposable exercise of religion, a free-speech right to determine what to show, and a \”constitutionally protected due process right to control the upbringing and education of the children.\” On April 18, a state judge overruled the new guidelines on procedural grounds, however the issue remains a live one; the state has said it \”will determine the right next steps.\”

The whole fight hinges on language in New York's state education law requiring that non-public schools offer an education that's \”substantially equivalent\” to that of the public schools. The origins of that language help uncover the issues on the line.

If the present controversy is to some degree an intra-Jewish dispute, it's being struggled the backdrop of education law which was largely shaped by a conflict between Catholics and Protestants within the other half from the 19th century-a battle over charge of tax dollars for education.

Nationally, the key figure in that fight was James G. Blaine. The son of the Presbyterian father along with a Catholic mother, Blaine served as a congressman from Maine, Speaker of the House, a U.S. senator, secretary of state, and, in 1884, the Republican Party's presidential nominee. Today, though, he's most widely known for championing a constitutional amendment in 1875 stipulating that \”no money raised by taxation in almost any State for that support of public schools, or derived from any public fund therefor, nor any public lands devoted thereto, shall ever be underneath the charge of any religious sect.\”

The federal Blaine Amendment failed, however the effort gone to live in the states, 38 of which adopted some type of it in their own constitutions (see \”Answered Prayer?\” legal beat). Inside a 2000 opinion, Mitchell v. Helms, four justices from the U.S. Supreme Court noted the things they called the \”shameful pedigree\” from the Blaine Amendments, adding that the national one was considered \”at a time of pervasive hostility towards the Catholic Church and to Catholics generally, also it was an open secret that 'sectarian' was code for 'Catholic.'\”

In New York, a key figure in the storyline from the Empire State's Blaine Amendment was Joseph Hodges Choate. Choate, a graduate of Harvard College and Harvard Law School, was from Salem, Massachusetts, a member of exactly the same family whose name has survived on the Choate Rosemary Hall School in Connecticut and the Choate Hall & Stewart law practice in Boston. A portrait of him, an oil painting by John Singer Sargent, hangs today in a prominent location at the Harvard Club of recent York.

Choate was known for his \”lasting distrust from the Ny Irish like a political force,\” as D. M. Marshman Jr. wrote inside a 1975 American Heritage profile of the man. The writer put the kindest possible face about this bias, attributing it to Choate's reaction to racist Irish violence against blacks within the 1863 New York draft riots: \”He considered them largely responsible for the hangings and tortures that caused countless black women and men to die violently and was bitter because neither Governor [Horatio] Seymour, elected with Irish votes, nor Archbishop [John] Hughes himself made any real effort to prevent them.\”

In March 1893, in New York City, Choate delivered an after-dinner speech on St. Patrick's Day to an Irish American social and charitable group. With lots of Irish Americans supporting the campaign overseas for Irish sovereignty, Choate-the \”embodiment of pure English stock and the Republican Party, that is, of what his audience most opposed,\” as Marshman put it-told the audience that the smartest thing to allow them to do was \”with your wives as well as your children, as well as your children's children, with the spoils you have taken from America in your hands, set your faces homeward, land there and strike the blow. . . . Think what it would mean for both countries if all the Irishmen of America . . . should march towards the relief of the native land! Then, indeed, would Ireland be for Irishmen and America for Americans!\” The remarks didn't earn laughs, though Choate maintained he jested.

A year later, Choate, speaking at a Republican meeting at Cooper Union on the topic of \”Tammany Rule,\” declared, \”We are tired of being listed in the despotic charge of a number of foreigners who've no stake in the soil.\” Catching himself, he quickly stated that the Republicans \”should be just as fed up with it if they were not foreigners.\”

In May of this year, Choate, then 62, was elected president from the Ny State Constitutional Convention. At the time, the New York Times was on high alert for anti-Catholic bigotry. The newspaper reported on a cartoon that the anti-Catholic American Protective Association had mailed to every convention delegate. The drawing depicted a monstrous snake labeled \”Catholic Church,\” and also the Times named it a \”rabid and vicious\” attack, comparing its vitriol to the hatred exhibited by the New England witch burners in Choate's hometown. Within the same article, a Protestant minister was quoted as saying: \”They [the Catholics] only teach the kids in their parochial schools to sing 'Hail Marys.' That doesn't benefit them any. . . . We do not want such systems in our public schools.\”

The delegates gathered in the assembly chamber in Albany have there been to tackle not only the pressing matter of defunding Catholic schools, but a variety of other hot-button problems with the late 19th century: Canals. Railroads. Indians. Prohibition. Women's suffrage. All 175 delegates were men, and largely in opposition to granting women the right to vote, though they did hear from Susan B. Anthony and Jean Brooks Greenleaf, whose husband would be a congressman from Rochester.

The convention's work continued for months. It concluded with a compromise between your aims of Catholics, who hoped to secure funding for his or her schools and charities, and those who opposed these kinds of support from tax dollars. The Catholics got funding for his or her charities but not their schools. The convention's education committee reached the following text: \”Neither the state nor any sub-division thereof shall use its property or credit or any public money, or authorize or permit with the idea to be used, directly or indirectly, in aid or maintenance, apart from for examination or inspection, associated with a school or institution of learning wholly

or in part underneath the control or direction of any religious denomination or in which any denominational tenet or doctrine is taught.\” New York's Blaine Amendment was created.

At the same time, their state also added to its education law the necessity that the non-public schools offer an education that is \”substantially equivalent\” to that particular of the public schools. That measure was referred to as Pound compulsory education law, after its primary sponsor, Cuthbert Winfred Pound, a Republican lawyer from Lockport, in western Ny, and the second cousin, once removed, of Roscoe Pound, who would become dean of Harvard School. In reporting the legislation's passage, the New York Tribune wrote that \”the measure continues to be defeated in former years, owing to the fears of Roman Catholics that a compulsory education law would interfere with their parochial schools.\” Between the state Blaine Amendment and the Pound law, the overall mood for religious education was embattled, and defensive. Attempting to reshape the narrative, the same week the Pound law was enacted, New York's Archbishop Michael Augustine Corrigan invited a crowd of two,000 towards the opening of the display of parochial-school student art at the Grand Central Palace, a Manhattan exhibition hall. Under the page-one headline \”Catholics Are Patriots,\” the New York Sun reported the big event by noting that William Bourke Cockran, an Irish-born Democratic congressman, \”said he was amazed that only at that area of the nineteenth century it was found necessary to repel the charge that the Catholic Church was hostile to republican institutions.\”

In mid-October of the same year-1894-a Jewish French army captain, Alfred Dreyfus, was charged with treason. By December 22, he'd been convicted with a life sentence. What became referred to as Dreyfus affair was included in a Viennese journalist, Theodor Herzl, who later credited it with inspiring him to become the founder of modern political Zionism. Even though the false charges against Dreyfus were ultimately dropped, the affair, and other manifestations of anti-Semitism in Europe in subsequent years, spurred a wave of Jewish immigration to the United States. Nyc was the primary arrival point for these immigrants, most of them religiously Orthodox, who soon developed religious schools, synagogues, along with other community institutions.

From 1894 to 2012, the Jewish schools flourished under a relatively non-intrusive New York regulatory regime. The colleges, sometimes allied with Catholic ones, pressed with limited success for additional funding as well as at times for repeal of the Blaine Amendment. In 1973, the U.S. Supreme Court struck down a brand new York State program made to fund school building repairs and reimburse parents for religious school tuition, ruling in Committee for Public Education & Religious Liberty v. Nyquist that this program violated the very first Amendment's establishment clause.

Some from the bitterest legal flare-ups involved not Jewish private schools but public-school districts, including that of Kiryas Joel, a Hasidic village about 50 miles northwest of Manhattan. In 1994, the U.S. Top court struck down as unconstitutional the state's creation of a college district whose boundaries corresponded with the ones from the village. However the \”substantially equivalent\” language wasn't much tested.

In 2001, the state established guidelines suggesting that local education officials make site inspections of non-public schools to research compliance only after \”a serious concern arises,\” and then once through an informal discussion with the school officials.

The legislative language from 1894, though, was answer to the complaint issued by Naftuli Moster in 2021. Moster was raised in Brooklyn as one of 17 children in a group of Hasidic Jews from the Belz sect, which is named following the town in Ukraine where the rabbinic dynasty that leads the group was founded in the 1800s. Moster attended Ny Hasidic schools until age 16, when he visited Israel to study. He told the Rockland/Westchester Journal News that from about the time he turned 13, he received no secular education whatsoever. He couldn't do long division or write an essay; he did not know exactly what a molecule or cell was; and he hadn't heard about the American Revolution, he told the New York Jewish Week.

In July 2021, Moster's group, Young Advocates for Fair Education, wrote to seven Ny school superintendents alleging that yeshivas within their educational districts offered \”poor quality and scant amount of secular education, particularly English instruction.\” The writers identified themselves as parents, students, and teachers at the schools who have been \”seriously concerned these yeshivas are not providing an education that fits the advantages of substantial equivalence.\” For the most part, they alleged, yeshiva students may be prepared to become familiar with a combined 90 minutes of English and math four times weekly, along with other secular research is ignored. All of this stops at age 13 for boys, and although Hasidic girls receive more secular instruction compared to boys do, the letter's authors said these were also concerned about whether Hasidic schools sufficiently prepare girls for his or her futures.

The group's complaint required your research of 38 schools in Brooklyn and one in Queens. A situation probe ensued, and then in early August, Mayor Bill de Blasio launched a city investigation from the schools. His spokesperson told the Jewish Week that \”there is zero tolerance for that kind of educational failure alleged.\”

By March 2021, after city investigators had visited more than a dozen from the Jewish schools, state senator Simcha Felder organized their state budget until his colleagues decided to amend their state law by further specifying what the state would look into determining \”substantial equivalence.\” Felder, an Orthodox Jew who represents Brooklyn's heavily Orthodox neighborhood of Borough Park, is really a Democrat who often votes with Republicans and therefore wields an important swing vote within the narrowly divided senate.

Felder's amendment set out two standards for nonprofit schools with bilingual programs: for elementary and middle schools, the state would consider whether

the curriculum provides academically rigorous instruction that develops critical thinking skills in the school's students, . . . including instruction in English that will prepare pupils to read fiction and nonfiction text for information and also to use that information to construct written essays that state a point of view or support an argument; instruction in mathematics that will prepare pupils to solve real world problems using both number sense and fluency with mathematical functions and processes; instruction in history by being in a position to interpret and analyze primary text to identify and explore important events in history, to construct written arguments while using supporting information they get from primary source material, demonstrate an understating from the role of geography and economics in the actions of world civilizations, as well as an knowledge of civics and also the responsibilities of citizens in world communities; and instruction in science by finding out how to gather, analyze and interpret observable data to make informed decisions and solve problems mathematically, using deductive and inductive reasoning to aid a hypothesis,

and the way to differentiate between correlational and causal relationships.

And for high schools, the amendment said, state officials were to consider whether \”the curriculum provides academically rigorous instruction that develops critical thinking skills within the school's students, the outcomes of which, taking into account the entirety from the curriculum, result in a sound basic education.\”

Felder's amendment was seen as an defense of the Jewish schools. \”Parents should have the ability to decide what type of education their kids receive,\” he told the New York Times in April 2021. But his success soon seemed to be a Pyrrhic victory.

In November 2021, state education commissioner MaryEllen Elia released guidelines for additional extensive general-studies offerings at private schools. The guidelines, including consequences for noncompliance, called on yeshivas to teach seven subjects to students in grades 1 to 4 and 11 subjects to 5th- to 8th-graders.

\”Adding up all the subjects and time requirements, a yeshiva will have to devote a lot more than six hours every single day, 5 days per week to secular studies,\” reported the Yeshiva World. The rules also called for that state to examine the colleges and warned that folks would face possible prosecution under truancy laws if they didn't withdraw their children from schools discovered to be failing. Those truancy laws call for fines and jail terms for parents found in violation; they might also trigger \”educational neglect\” charges that may culminate in children being taken away from their parents and placed in foster care, an organization home, or perhaps a court-ordered guardianship.

That same month, Rabbi Aaron Teitelbaum, the leader of the Kiryas Joel community of Satmar Hasidim, publicly denounced Elia, saying that she'd \”conspired with traitors and also the wicked to persecute\” a Jewish community \”which only really wants to educate its children relating to Torah and tradition as has been from one generation to another.\”

Teitelbaum, speaking days prior to the onset of Hanukkah, compared Elia towards the villains of the Maccabees' era in the second century BCE, accusing her of wanting to \”remove us from your religion exactly as the Greeks wanted within their time, to eliminate the training institutions, a decree of extermination.\”

Said Teitelbaum, \”in a democratic country there's freedom of religion and they've no to interfere.\” He added, in remarks reported through the Yeshiva World, when Elia wanted to improve education within the state she should concentrate on the public schools.

In February 2021, shortly before filing suit, Parents for Educational and Religious Liberty in Schools noted that the Nyc education department was advertising two job positions devoted to enforcing the substantial-equivalency law: a professional director and a senior operations director. The duties of the operations position, having a earnings of $125,256 and up, included determining whether 250,000 students at 800 religious or independent city schools get a substantially equivalent education and managing a team for college visits, monitoring curricula, and reconnaissance work. The chief post requires someone having a \”solid understanding\” of state educational standards and practices but mentions nothing about fluency in the diverse values, culture, and languages from the schools.

With the state's new guidelines now on hold, it remains to be seen whether those positions is ever going to be filled. If they are, and the new hires walk-through the doors from the yeshivas, what will they see?

The answer depends on whom you ask.

Rabbi Ysoscher Katz, chair from the Talmud department at the Modern Orthodox (sometimes called \”Open Orthodox\”) rabbinical school Yeshivat Chovevei Torah, grew up within the Satmar Hasidic sect but now identifies as Modern Orthodox. He called the secular studies of his childhood \”literally abysmal,\” and said his impression was that teachers were concerned that such training would expose students to the secular world, which they saw as morally corrupt.

A significant number of those classmates graduated not able to write a sound English sentence and without knowing what \”medieval\” and \”Renaissance,\” let alone the main difference forwards and backwards, Katz said. \”I knew nothing about science,\” he added.

Inspectors today, Katz said, would likely discover that the secular education provided by the Hasidic schools has deteriorated even in the level he and the classmates experienced. Recently, Hasidic schools have replaced non-Orthodox teachers and the occasional non-Jewish one with Hasidic instructors, Katz said, contending these non-credentialed, untrained Hasidic teachers leave today's students less prepared for work and better education than their parents and grandparents were.

A contrasting view originates from Moshe Krakowski, an affiliate professor at Yeshiva University and director of the Jewish education master's program at its Azrieli Graduate School of Jewish Education and Administration. Krakowski's studies have taken him on appointments with schools of several different Hasidic varieties.

\”One of the biggest misconceptions is that [students] don't get any secular education. That's not true,\” Krakowski said. \”There is not a single Hasidic school that does not offer secular education a minimum of through 8th or 9th grade. We aren't referring to zero secular education for anyone.\” Following this article was published online, Krakowski contacted Education Next to explain that there is one school that doesn't offer formal instruction in English writing, grammar, or spelling but said that it had been an outlier.

Not only are schools offering secular studies, Krakowski said, but the training is much more than sufficient for students' needs. The secret kosher sauce, he explained, is study from the Talmud, the Hebrew and Aramaic writings on the Jewish Bible codified between your second and sixth centuries. Rabbis teaching Talmud don't quite ask the same sorts of questions that university professors do, but they often cold-call upon their students to probe sophisticated questions regarding ancient and medieval texts. And like law professors, they often times ask follow-up questions that require students to articulate arguments in a manner that demonstrates their grasp of essential points.

\”These are stuff that, honestly, college kids and even graduate students have a problem with,\” Krakowski said. \”They can't really do the sorts of stuff that these kids can perform pretty much.\” (With a doctorate from Northwestern University and a bachelor's degree from the University of Chicago, Krakowski is familiar with some of the nation's most elite schools.)

Krakowski asserted, ironically, the state pressure might be counterproductive, because it came at any given time when, in the estimation, some Hasidic communities were organically nudging schools inside a direction of offering more-substantial secular studies. \”When you start pushing from the outside and imposing regulations from the outside, it becomes treyf,\” non-kosher, he said. Even people in the city who would like more secular education \”are not likely to pursue it, since it is associated with the ex-Hasidim and the government and also the evil outside people who are pushing against us. Ironically, you end up harming the development of a more-robust secular education by doing that.\”

One day earlier this year, I spent nearly 3 . 5 hours touring in regards to a dozen classes-grades 3 to 7-and speaking with administrators, students, teachers, parents, and alumni at two Hasidic schools in Brooklyn. One of these was among the list of 39 schools that Young Advocates for Fair Education flagged as failing. Both asked not to be named in this article.

In one of the schools, the students stood respectfully when my guide-an Orthodox but non-Hasidic rabbi and chair of the secular studies program, who holds a graduate degree from Yeshiva University-entered the area. Inside a 7th-grade class, an infectiously enthusiastic teacher saw 25 hands shoot up as he sought two volunteers. Two lucky kids found the leading of the room, where the teacher had hung a world map. He acknowledged the map, which he'd reclaimed from the public-school discard pile, still included the Ussr.

\”It still works,\” he quipped.

The teacher quizzed the boys within an apparently impromptu competition, asking them to discover Sri Lanka; a location where the Usa lost a war; probably the most populous nation in the world; and also the Horn of Africa. The duo handled each task with ease-faster than I probably could have. One student erred once the teacher asked the class to name a major Sri Lankan export, but another were built with a correct response: tea.

\”When a class like this, and also the children are engaged, and that i read an article on the contrary, it breaks me,\” the secular studies coordinator said to me as we left the room.

In most ways, the classrooms and facilities I saw were no not the same as any of thousands of others one might visit across the nation. The halls had water fountains, and backpacks, school supplies, and colorful signage abounded. The only details that appeared to set these schools apart were the students' (and lots of teachers') skullcaps, side curls, and ritual fringes. When Gerry Albarelli, a non-Jew, was considering employment offer from the Brooklyn Hasidic school where he'd teach for five years, he was warned through the hiring principal to think of it as likely to Mars. \”These boys reside in a very insular world. Not one of them has a tv,\” he was told, as he later recorded in the book Teacha! Stories from the Yeshiva. \”They speak Yiddish in your own home; some don't speak any English whatsoever. We're up against the impossible.\” Albarelli did face challenges, but he also made a large amount of progress teaching the boys.

An alumnus of one from the schools I visited, a lawyer, told me that studying for that bar was easier for someone used to spending long days poring over books. So when fellow law students became frustrated trying to tease meaning out of impossibly complicated tax-law codes, he was reminded of studying certain Talmudic volumes that address laws similar to torts.

Rabbi Chaim Dovid Zwiebel, executive vice president of Agudath Israel of America, a virtually century-old advocacy organization for U.S. Orthodox Jewry, also asserted his Talmud instruction growing up helped him in school. \”I would not state that about trigonometry or the good reputation for the Ming dynasty, which I learned in high school rather than used,\” he explained.

At both yeshivas, I observed and heard nothing in my interviews suggesting anything but two communities striving to instruct young people as best they knew how, inside the context of the religious values they hold dear. \”We're not in the industry of wasting people's time, and whether that's Judaic studies or secular studies, we absolutely think that it must be done well,\” a principal explained. \”It's nothing like secular studies is a secondhand activity that occurs after the day, like some kind of afterschool program.\” Yet that's precisely what critics allege.

Any school could stage a two-hour charade for a journalist's benefit, and it is definitely not uncommon for schools and colleges to closely guide a reporter's visit. But my impression was that what I heard and witnessed at both of these schools was genuine. At one of the Hasidic schools, I had been able to talk to any students I selected, and also at the other, I did not speak directly with students but talked with parents and alumni without restriction.

I spoke with 3rd graders writing essays in English about the upcoming Jewish holiday of Purim, and I found their conntacting be clear and largely error-free. Students I selected randomly happily answered my questions, and when I feigned ignorance concerning the holiday's story, they showed me the things they were covering.

In a teachers' lounge, webmaster talked me through an elaborate, color-coded software program, which the school uses to track students' progress in each and every subject on the highly granular level.

I spoke in more detail with a mother, Sarah, whose son is a 3rd grader at the Hasidic yeshiva from which his father graduated. \”My son is an active, cute, rambunctious thing. The fact that his teachers will keep this guy engaged somehow until 5 p.m. is a miracle,\” she said. Her son is reading Andrew Clements's children's novels, which in a public school would be on his grade level. Sarah said she didn't teach him to read in English. \”He's in a position to see clearly and repeat the story back to me and describe the plot and also the characters in detail,\” she said.

The secular studies coordinator explained that in the first years on the job, boys would demand to know why they have to learn certain general-studies information. \”There's usually a good answer, because if I can not answer it, it shouldn't be taught,\” he explained. A group of mothers asked for a conference to discuss curriculum. They demanded to know: \”What are you doing to ensure that my child has a better chance at supporting his family than my husband does?\” The coordinator explained what he was attempting to accomplish using the secular studies curriculum, noting that preparing the boys for jobs ended up being to be his focus.

These sorts of questions from parents, said Sarah, come amid a shifting tide within the Hasidic world, where many parents increasingly want their children to have better general-studies skills than they have themselves. Yet clearly, many families still value the faith-based education offered at Jewish schools, despite the fact that, like the majority of private education, it may be expensive. Tuition in the schools is generally $16,000 nationwide, but can exceed $35,000 at some New York yeshivas, according to the Avi Chai Foundation, that has done research on financing Jewish education; New York City's annual per-pupil spending in public schools was $25,199 in 2021, based on the U.S. Census Bureau.

What has changed since 1894? Perhaps not a few of the religious instruction in the Jewish schools, and certainly not the Jewish texts being studied, some of which date back hundreds, even 1000's of years. What is different, though, is who helps make the laws of New York State. Whereas in 1894 it had been Protestants like Choate and Pound who wielded power, today the state has a Catholic governor, Andrew Cuomo, and it is legislature includes the influential Orthodox senator, Simcha Felder.

But if Jewish and Catholic politicians have gained power previously 125 years, the hold that traditional religion is wearing Americans, as measured by regular attendance at religious services, has eroded recently. In 2021, the Pew Research Center noted that 36 percent of american citizens report weekly religious service attendance, down three percentage points from 2007; between 2007 and 2021, the percentage of U.S. adults who never or rarely attend religious services rose to 30 % from 27 %.

Given this decline in religious observance, some see the New York probe of yeshivas poor broader infringements by secular or liberal society on traditional religious institutions. In that analysis, the present regulatory effort to judge the academic offerings of Hasidic schools seems like just the latest development in a long government push against minority religious education. In 1894, authorities took away funding. In 2021, they're sending inspectors into schools to check on them.

Zwiebel, from the Orthodox Agudah, sees the present criticism of Hasidim in the context of a recent surge in anti-Semitism reported by the Anti-Defamation League. Referring to Hasidim as \”insular\” implies suspicion about what happens behind closed doors, he said. \”There's an over-all perception out there that somehow children who grow up in this community are now being kept in the dark and the Dark Ages to control them,\” Zwiebel said from the Hasidim.

It's entirely possible that the present conflict might trigger further revision of New York education law, or maybe even repeal of New York's Blaine Amendment. A showdown within the state amendments might happen soon in the U.S. Top court, because the court has decided to hear a Montana case dedicated to their constitutionality.

As for substantial equivalence, the bounds of state authority over private schools have yet to be fully tested. Most likely, the field will have out in the courts. In Wisconsin v. Yoder, the final Court ruled in 1972 that Amish families had a First Amendment right to end their children's formal education in the 8th grade, however the ruling was somewhat narrowly tailored.

Zwiebel said the fracas over New York's Jewish schools should lead the educational establishment to reexamine some fundamental questions, such as the reason for education.

\”I hope the commissioner of education is asking herself that today,\” he explained. Education really should not be by what law books have said it should be for a century, or substantial equivalence, he explained. \”It's a dumb method of doing it.\” Instead, educational facilities should make an effort to create lifelong learners. That's something most of the yeshivas do quite well, Zwiebel noted, and of that they are extremely proud. Whatever their graduates' English-language skills are, many still pore over religious texts daily, long afterwards they've graduated from yeshiva.

It's enough to boost the issue: When the state does revisit its education laws, maybe it should consider reversing them-requiring the public schools to become substantially equivalent to the religious ones rather than the other way around.