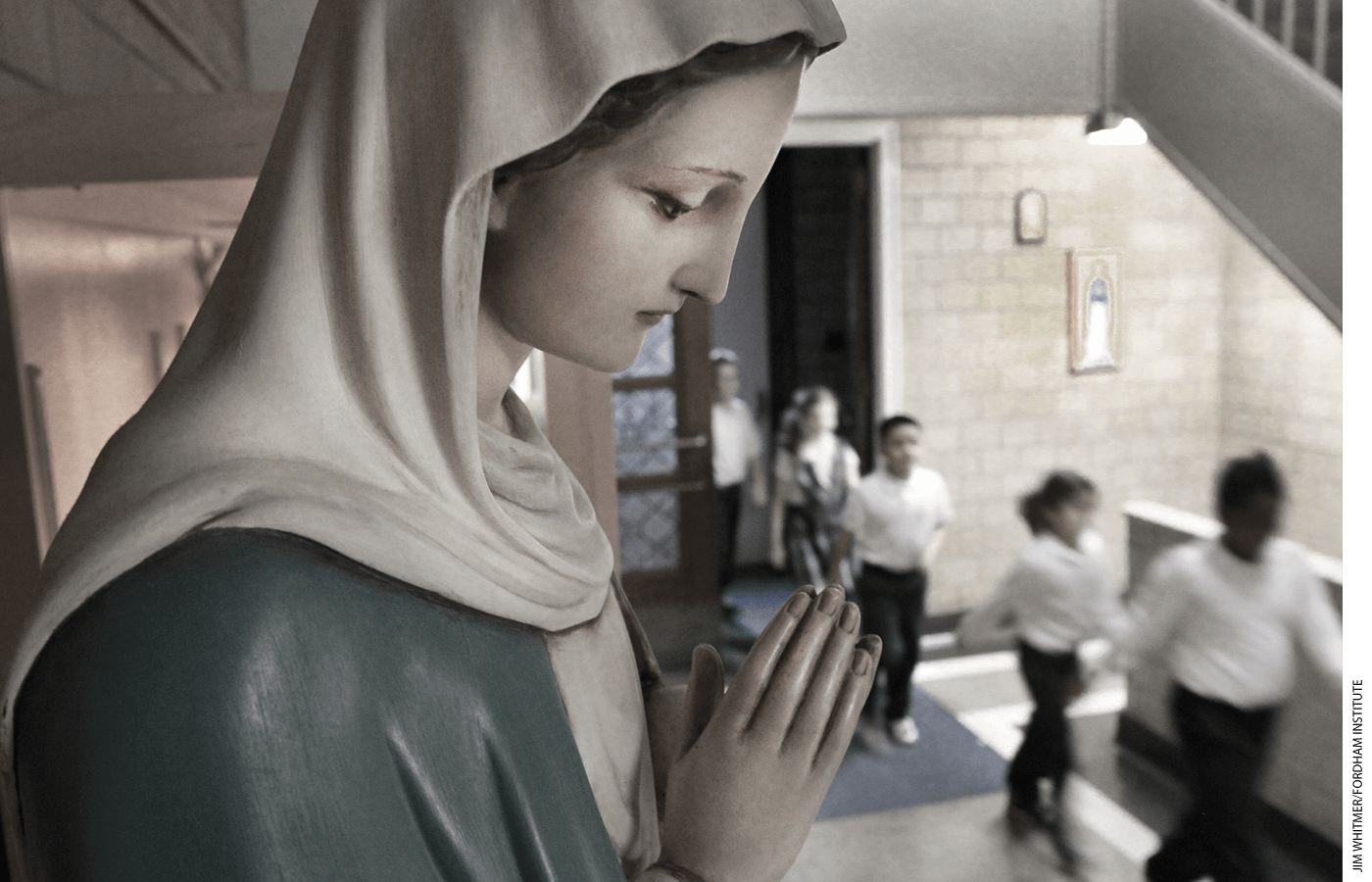

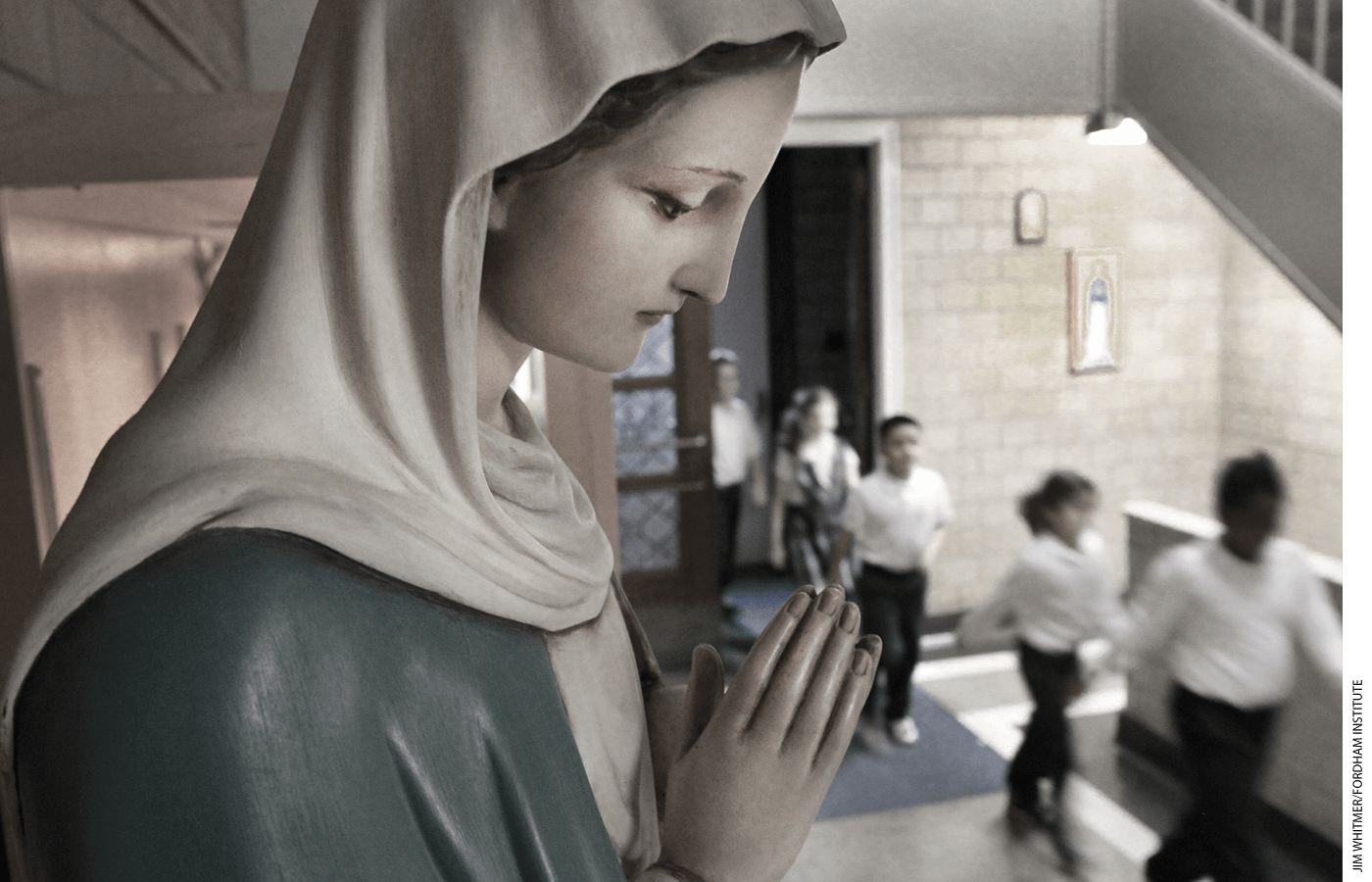

Catholic schools have dealt with declining enrollment and rising costs because the 1960s, leading to widespread closures that were accelerated by the pandemic (See \”In Pandemic, Private Schools Face Peril,\” Features, Fall 2021). To help Catholic schools regain their financial footing, Seton Blended Learning Network, a program inside the nonprofit organization Seton Education Partners, has partnered with schools to advertise blended learning and increase enrollment at a faster pace.

The main driver of Catholic schools' present plight continues to be their human capital model. Historically, Catholic schools relied upon people in religious vocations, like priests and sisters, to teach students. They'd the gravitas, the support of oldsters to show large classes, and also the religious commitment to take really low salaries. As religious vocations declined, Catholic schools needed to turn to lay teachers and administrators, increasing costs and decreasing class sizes.

Small class sizes are now a feature of numerous Catholic schools across the country and a selling point for moms and dads. However , small the class size, the higher the per-pupil expense, even when the salaries of the staff are well below the ones from the workers in many public schools. Designed for schools that are looking to serve low-income populations, and even for schools that want to serve middle-class families, this makes the financial model problematic.

Seton Education Partners is working with 14 Catholic schools around the country to change that equation. As Emily Gilbride, director of the network, said: \”We will reduce their per-pupil operating costs.\” In the schools where Seton works, it encourages classrooms to grow, often to an average of 30 students per class, up from 15. To deal with these additional students, courses are split into two or three smaller instructional units that progress throughout the day with what Gilbride calls a \”rotational small-group model.\” While one group is dealing with the teacher, others take presctiption Chromebooks, dealing with computer-adaptive software like i-Read, Imagine Math, and Lexia Learning. Seton uses 14 different software platforms in all, with respect to the school, grade, and student need.

A more half the category is on computers at any given time, so Seton partner schools only need a two-to-one ratio of children to Chromebooks, rather than the more expensive and intensive one-to-one programs that lots of schools use. This model also requires little change to the physical structures of faculties and classrooms. Usually, Seton just adds some tables along one classroom wall for everyone as computer stations, plus some kidney-shaped tables for small-group use teachers.

St. Joseph Catholic School in Cincinnati, Ohio, was able to grow to 282 students from 202 in the initial year of partnership. As most of those children take part in Ohio's EdChoice school voucher program, each additional pupil represented $4,650 in new revenue for that school. All in all, that meant almost $400,000 more entering the college on an annual basis.

The newest accessory for the Seton portfolio, the Immaculate Conception School in Dayton, Ohio, could increase its enrollment by 90 students in its newbie of partnership. Again, what this means is hundreds of thousands more dollars in revenue every year. For small Catholic schools, this can be a massive swing in enrollment and revenue, along with a massive chance to serve more students.

Moving to larger classes and blended learning was not easy, however. Both mom and dad and teachers need convincing, and teachers need training and technical help. With respect to parents, Gilbride argues that concentrating on personalization through computer-adaptive software is a big selling point. Also, schools don't double their class sizes overnight. Usually, they give a few children per year, which cushions the shock, allowing parents to ease in to the new model. The storyline for teachers is comparable. By easing in to the model, providing instructional coaches for that first two many years of partnership, and focusing on the upside, Seton can win teachers over. If the partnership helps prevent a school from closing, it means that teachers keep their jobs.

\”We want to place each child's God-given potential at the forefront of what we're doing,\” Gilbride says, which will help focus each family and teachers on which is essential.

Seton's partnership is really a multiyear agreement with schools to assist get blended-learning programs up and running and to support schools as they transition to operating the programs independently. Seton fundraises for the startup costs from the transition, which could range from $600,000 for any small school to $850,000 for a larger one. These funds goes toward purchasing hardware and software, upgrading servers and wiring, and employing an instructional coach for teachers. After that, schools pay a charge to the network to carry on to participate. Seton says its bulk paying for software licenses, which are then distributed around network schools, saves participating schools more than they pay in network fees. Software licenses are costly.

For the Seton model to work, however, several stars need to align. There has to be leadership in the school willing to do something different. There has to be someone who understands the need to increase revenue at a faster rate than expenses. There must be teachers and fogeys willing to buy in. The model requires not only a shift to blended learning, but a college culture centered on doing different things to balance your budget and educate children. Its not all school has this kind of leadership or community.

Blended learning is not for everybody, but Gilbride offers two lessons that affect public and private schools alike.

First, schools seeking to try blended learning need not arrange for one-to-one student-to-device ratios. The one-to-one phenomenon has swept the nation, and schools happen to be purchasing huge numbers of tablets and Chromebooks to satisfy demand. These devices require updates to servers and routers and sometimes even electrical wiring in schools. Tablets should be maintained, plus they require technical support, and the higher the number of these devices is, the larger those associated cost is. Yes, if class sizes are increasing or other changes are now being made, then your proven fact that youngsters are getting their particular computers or tablets might help blunt criticism. But blunting criticism for the short term isn't well worth the trade-off in the long run.

Gilbride argues that a two-to-one ratio is better. Her primary argument is it \”allows teachers to teach.\” Rather than having students constantly glued to devices, students use devices at sometimes and do not rely on them at others. There's here we are at traditional instruction or small-group work and time for you to work with adaptive software. This structure allows teachers and software to complete the things they each do best.

Two-to-one is also undeniably cheaper. Buying, supporting, and looking after half the amount of devices of a one-to-one program can represent serious financial savings. For schools with very narrow margins in their budgets, this can be a gamechanger. You may still find substantial startup costs, though, and Seton needs to do fundraising around the front-end to make the transition.

Second, Gilbride encourages schools to begin small. The software itself do not need to cost much. Numerous free, high-quality software packages have many from the options that come with the software that Seton and other blended-learning providers use. They aren't as fully articulated because the paid programs, but they can give schools a tough concept of what teachers and students can do when they switch to a blended model. These include ISL, No Red Ink, and, perhaps including, Khan Academy.

Transitioning to a blended model is a big shift for students, teachers, leaders, and fogeys. It is not something which should be done lightly or quickly. It can go wrong, as some schools learned with attempts to shift instruction rapidly online amid the pandemic. Schools curious about the approach can try blended learning with these free tools in one classroom or grade to see how the model works, rather than scale as much as the whole school immediately. Teachers and principals can dip their toes within the water and see what the temperatures are. Do teachers such as the model? Are children answering it? What are the practical concerns, for example infrastructure upgrades, schedule changes, and so forth? In short, is this something really worth trying on the larger scale? Once an effective pilot program will schools desire to make the big investments in equipment and training to maneuver entirely to a blended model.

These lessons apply beyond blended learning. Any decision to make use of technology should focus on the problem that technologies are attempting to solve. No matter what we've got the technology of tomorrow will be, starting with small pilot programs is really a wise first step for schools. Also, considering how students can share resources, rather than requiring one device for every child, can be a method for saving costs.

Blended learning isn't just for schools facing fiscal difficulty or on the verge of closure. It can also be of use to rural schools that have difficulty recruiting teachers for higher-level math and science courses which desire to provide challenging coursework for additional advanced students. Blended learning can change more than just the economics of a school; it can also change the excellence of the education a school provides.