The Institute of Notre Dame, a 170-year-old Catholic girls' school in Baltimore whose graduates included Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi and Senator Barbara Mikulski, announced in May it would close.

\”Sad news,\” Pelosi tweeted. Mikulski named it a \”treasured institution.\”

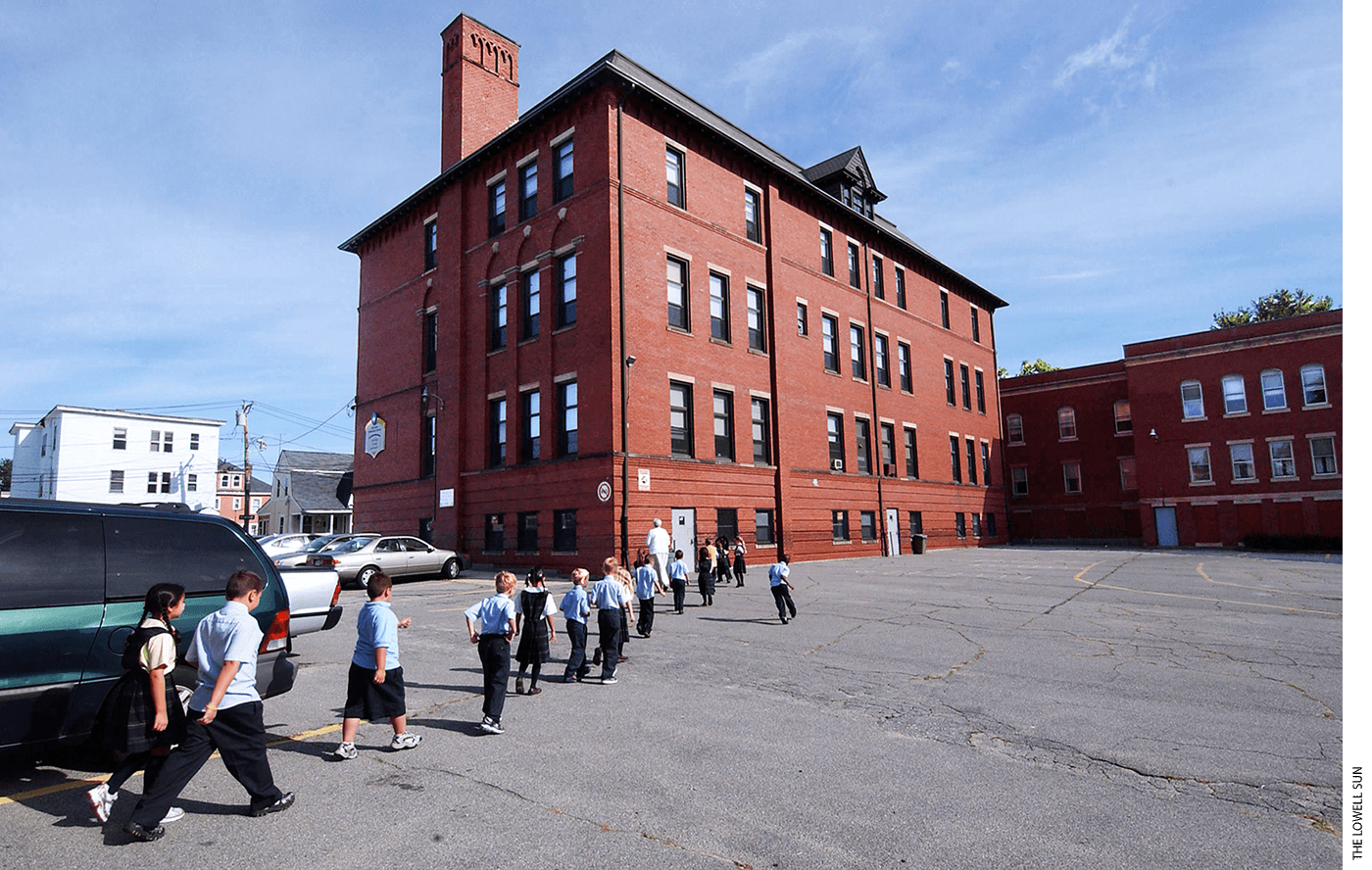

The Covid-19 pandemic has accelerated the amount of urban Catholic and other private schools which are closing amid financial pressure and dwindling enrollment. Unlike popular understanding, many private school students are from middle- and low-income families, and many private schools are expressly dedicated to serving them (see Figure 1). By July 9, a Cato Institute tracker listed 97 private schools that had announced permanent closures attributed at least partially towards the pandemic.

Such closures are an important part of the story of how the pandemic has affected private schools. But the tale isn't entirely certainly one of weakness. Other schools have used their autonomy, flexibility, and powerful family and community relationships to deliver robust distance education.

The right policy choices can now help ensure that private schools remain viable alternatives for families, even while all schools enter a period of newly constrained resources.

As the landscape rapidly shifted this spring, the middle on Reinventing Public Education and the American Enterprise Institute were fast out of the gate with data collection and analysis. CRPE began publishing data on school-district response plans in mid-March. AEI began conducting longitudinal surveys of districts not much later. EdChoice, Echelon Insights, Education Week, Pew Research, yet others have also tracked student, teacher, and parent perspectives and experiences.

Several of these efforts provide insight into private schools. Morning Consult and EdChoice surveyed teachers across private, charter, and district schools. Hanover Research and EdChoice surveyed private school employees across the nation. The Association of Christian Schools International surveyed their members in the usa. Recently, the Education Next survey gathered data from parents across district, charter, and schools, and the National Center for Research on Education Access and selection published an analysis of three,500 district, charter, and private school websites.

The data paint an incomplete picture of methods private schools have fared within the crisis to date, but they do suggest considerable variation. Each morning Consult/EdChoice survey, 48 percent of non-public school teachers indicated they were providing e-learning, 32 percent said these were providing at-home assignments, and 16 percent said they weren't providing either. The Hanover Research/EdChoice survey (that about 3 in 10 responses came from private schools in Florida) also shows variation among private schools. Overall, 88 percent of non-public school employees reported their schools had shifted to online learning with formal curricula, including 92 percent of Catholic private schools and 65 percent of nonreligious private schools. Schools answering the survey through the Association of Christian Schools International reported variations in distance education, too. A majority of schools reported providing three to five hours each day of distance learning, though high schools often provided many elementary schools often provided less.

Anecdotal accounts make sure private-school responses towards the crisis run the gamut. On one end of the spectrum are schools that have been not able to sustain operations past the current school year. Numerous media accounts have noted private schools that have closed not only for the school year, but permanently. In addition to the Institute of Notre Dame in Baltimore, included in this are All Saints Catholic School in Wilmington, Delaware; four schools within the Archdiocese of Galveston-Houston; at least 10 schools in Nj; and 20 schools within the Archdiocese of recent York, among others. The Archdiocese of Galveston-Houston described how the pandemic influenced its decision to shut schools: \”In recent weeks, the reality of our budget challenges, drastically and negatively compounded through the Covid-19 protocols, forced a reassessment of those schools' viability. . . . These dire circumstances have forced our hand.\”

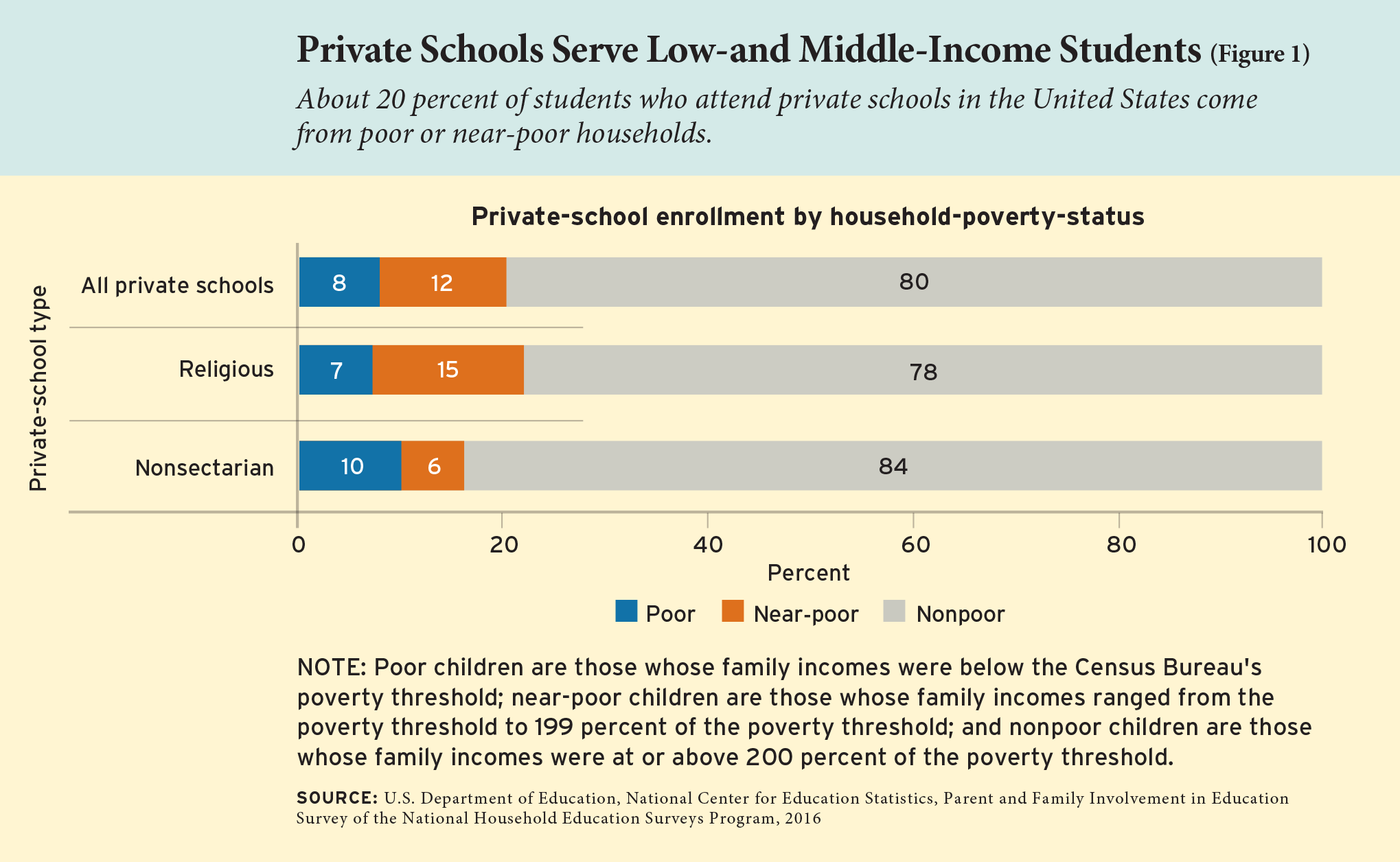

On another end of the spectrum are private schools that entered the pandemic in positions of relative strength. Partnership Schools, a network of nine Catholic schools in Nyc and Cleveland serving predominantly low-income students, found itself at the epicenter from the outbreak. Superintendent Kathleen Porter-Magee recalls the week of March 9 like a sprint to anticipate and adapt to conditions that changed by the hour. The network's response pivoted quickly from procuring supplies and sanitizing buildings on Monday to, by Wednesday, planning to close their buildings for that near future. \”We had war room meetings every morning and sent email communications every afternoon,\” Porter-Magee said, \”and sometimes that still didn't feel like it was fast enough.\”

In a procedure that involved pivoting on the daily and hourly basis and ascertaining families' needs for devices and Internet access, in addition to a few all-nighters, Partnership Schools could send students home on March 13 having a week's price of pencil-and-paper material. The week after, the schools presented a remote-learning plan they continued to iterate and tweak with the end of the school year.

The majority of private schools likely lie approximately these two extremes, muddling through as well as they can during an unprecedented disruption. Within the words of Frank O'Linn, superintendent of faculties for that Diocese of Cleveland, \”Like a lot of crises, it's a test. It's revealed lots of strong schools and some phenomenal stories . . . but not all are phenomenal.\”

What factors influence whether a school fails or flourishes under extreme duress? Common sense, along with the literature on crisis management, suggests that a school's ability to respond and adapt in the midst of a crisis likely depends upon three broad

factors: autonomy and adaptability, family and community relationships, and financial resources.

Some have been quick to posit that private schools (and charter schools) happen to be nimblest within their response to the shutdown. There are some data consistent with this claim. On the 2021 Education Next survey, parents of nearly 70 percent of private school students said their children met virtually with their school or teachers as well as their classmates several times per week. Parents of just 43 percent of district students said exactly the same. Private school students were also more likely to receive instruction that included new content, as opposed to all review material.

Other data complicate this narrative, however. The analysis from the National Center for Research on Education Access and Choice suggests that charter and district schools did more to support some facets of learning, such as \”personalization and engagement outside of class.\” Ultimately, assessing the potency of school responses will need further research not only how schools responded but how much students learned (or didn't learn) consequently.

In the meantime, it's useful to explore how the autonomy and flexibility of private schools may have affected remarkable ability to reply effectively. Leaders of non-public schools typically have direct oversight and authority over not just curriculum and instruction, but additionally human resources, operations, and finances. Many non-Catholic Christian and nonsectarian schools operate independently from the larger system. Even Catholic schools, which operate under the purview of the Church, benefit from a powerful adherence to \”subsidiarity\”-the principle that matters are best handled at most decentralized level possible.

However, autonomy and adaptability may also leave the leaders of person schools adrift and isolated whenever a crisis hits. Frankie Jones of the University of Notre Dame's Alliance for Catholic Education Academies and Mary Ann Remick Leadership Program has witnessed \”a lot of principals searching for help and guidance\” and efforts in the Church to keep school-leader autonomy while providing support. To assist school-level leaders and staff, for example, some dioceses have created virtual spaces to talk about ideas and challenges, trained teachers to make use of virtual-learning platforms, or provided assistance with how schools should prioritize family and student needs. Church policies impose relatively few regulatory burdens and governance structures on schools, thereby pushing decisions to the local level. But intentional efforts to inform, guide, and support local decisionmakers are necessary for this degree of flexibility to work.

When you are looking at family and community relationships, private schools could also possess a leg up. The religious orientation of numerous private schools often ties these to local churches or synagogues and includes theological principles that prioritize family engagement and repair to the community. Family relationships really are a central element of Catholic schools, for instance, because church doctrine establishes parents as children's primary educators. Kathleen Porter-Magee describes Partnership Schools' approach to the crisis: \”We ramped up our academics, but we led first and foremost by connecting with families to determine the way they [were doing]. . . . That community-first approach is really what paved the way in which to keep learning going.\”

Private schools also provide a motivation to build strong relationships with families and also the community because a lot of their revenue depends on families deciding to enroll their children and also to contribute even modest sums to tuition. Mary Menacho, the interim executive director from the California Association of Independent Schools, said that the 2008 recession helped prepare private schools for today's crisis. Since 2008, she said, \”independent schools have had to look at what their value-add is, hone their mission, and clarify what sets them apart. That has been the basis for strong relationships with their families-clarity on which schools are providing and what means they are distinct.\” It makes sense that private schools that have invested in building relationships and communicating their distinct value proposition to people are positioned to partner with families to support students learning from home.

While private schools might benefit from autonomy, flexibility, and strong family and community relationships, however, they mostly lack access to taxpayer funds and frequently work on shoestring budgets. Even the nimblest schools using the strongest family and community relationships will find on their own the ropes if they don't have cash on hand to purchase cleaning supplies, buy and distribute devices, print learning materials, or procure virtual-learning platforms. A highly effective response requires money, and lots of private schools-especially those dedicated to serving middle- and low-income families-were already on shaky financial footing leading into the coronavirus crisis.

In the Hanover/EdChoice survey, about 4 in 10 private-school respondents were \”extremely or very worried\” about collecting tuition for the remainder of the college year or about drops in philanthropic support, and roughly half were \”extremely or very worried\” about losing enrollment (see Figure 2). For some private schools, the financial effects have previously begun. Laptop computer conducted through the Association of Christian Schools International indicates that about one in five of the member schools provides tuition discounts or refunds, and more than a quarter have furloughed staff. About one-third of schools have re-enrollment rates less than those simultaneously last year, and most half report a decline in new student inquiries-an ill omen for that fall.

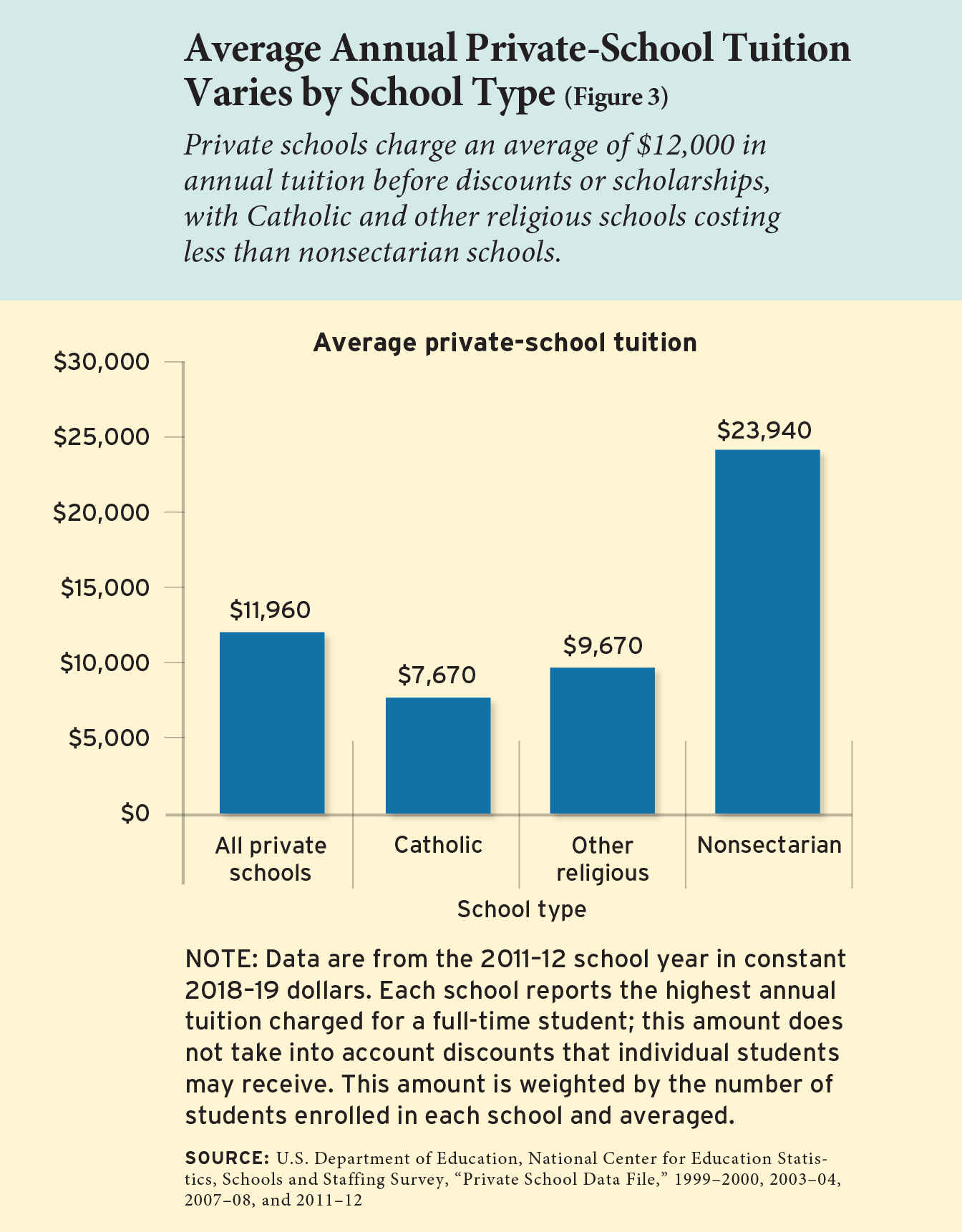

All told, the financial outlook web hosting schools is shaping as a severe challenge. Economic turmoil may make even modest contributions to school tuition untenable for a lot of middle- and low-income families (see Figure 3). Schools that depend on subsidies from churches receive less support when weekly in-person church services are canceled and offerings decline. Companies facing losses may cut corporate donations to tax-credit scholarship programs. Foundation assets are bound to take a hit, too, with implications for philanthropic support for schools and scholarships. Finally, as states resize their budgets, the chances are funding for education is going to be cut-with potential implications for voucher programs assuring education savings accounts.

Superintendent O'Linn of Cleveland put a fine point on the problem: \”When there is a system highly dependent on good will and philanthropy, and you've got not only the medical crisis but the economic crisis. . . . We're very worried about it.\” Many predict the task will be greatest for schools that are already small or underenrolled. Laura Colangelo of the Texas Private Schools Association said she sees underenrolled Catholic schools and small Christian schools as the most vulnerable. But, she said, \”independent schools and much more elite private schools are very cautious, too.\”

As the economic picture for that country worsens, the challenges of financial viability could easily outweigh the benefits of autonomy and family relationships. These issues are connected. Said O'Linn, \”We need the government to help with the funding. But when we don't supply the value proposition and also the family atmosphere, families won't choose us.\”

For all of the uncertainty wrought by the crisis, it's clear that lots of private schools serving middle- and low-income students will require financial support to survive. Financial support that maximizes autonomy and flexibility and leverages schools' family and community relationships is better still.

The federal government has taken steps to support private schools and students with the crisis. First and foremost, private schools can usually benefit from several facets of the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security, or CARES, Act, such as the $660 billion Small Business Administration Paycheck Protection Program. As of late April, many private schools-including 72 percent of faculties that taken care of immediately laptop computer conducted through the Association of Christian Schools International-were likely to participate. It's unclear the number of private schools have actually accessed Sba loans. Some private schools were reluctant to participate due to concern that accepting federal aid would require them to demonstrate compliance having a host of federal regulations.

Private schools may also get relief from the CARES Act's $31 billion Education Stabilization Fund, including $3 billion for the Governor's Emergency Education Relief Fund and $13.5 billion for that Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief Fund. Under both programs, districts will get funding to supply support to schools, including mental health services, technology, or cleaning supplies. Private schools can access these supports in the local school district but don't receive any funding themselves.

The distribution of money from the Governor's Emergency Education Relief Fund depends upon the priorities of governors, but states have less discretion within the distribution of cash from the Elementary and School Emergency Relief Fund. On June 25, U.S. Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos issued a binding rule based on how school districts must share this funding with non-public schools. The rule gives districts two options. The very first bases private-school support on the total number of all private school students residing in an area, as opposed to the quantity of low-income private school students. That approach contrasts using the way districts typically provide federally funded services to private schools, based on a Title I formula directing money to low-income students. This primary option in the DeVos rule would end up directing a lot more aid to private schools, but districts have another choice: they can share the money in line with the quantity of low-income students in private schools, as long as the district consequently directs its area of the funding exclusively to low-income students. This second option, however, would limit districts' flexibility in using the cash. Several state attorneys general, led by California's, have sued over the new rule.

Neither of these two funding programs is especially smartly designed to fit the particular strengths and challenges of non-public schools. First, while school districts are required to consult with private schools, private schools haven't much treatments for how the Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief Fund cash is used. This approach does not take advantage of private schools' autonomy and adaptability. Second, the rule around the distribution of funds to private schools may provide disproportionate aid to private schools, however it doesn't target help to the non-public schools most in need of that aid-those serving middle- and low-income families. Later on relief legislation, federal policymakers can perform more to ensure that funding is directed to high-need student populations, while also allowing the maximum flexibility for school-level leaders.

Alongside federal efforts to stabilize the education system, state policymakers also have an important role. Financial support for schools will likely be an issue of great debate in the next round of state budget negotiations. State policymakers will certainly work to preserve just as much funding as possible for public schools, but they should also consider the needs of middle- and low-income families enrolled in private-school choice programs.

Vouchers, tax-credit scholarship grant programs, and state education savings accounts are products of state regulations. 70 % of students who participate are in means-tested school-choice programs, available only to those with household incomes below a particular threshold. Many more participating students have been in programs that are only accessible to students with special needs or circumstances, such as learners with exceptionalities or in foster care. State policymakers eager to direct support to middle- and low-income families can start by preserving funding of these programs.

In doing this, they'll also help preserve institutions that, if lost, would send students flooding back to the public system-just as that system is navigating ongoing disruption and uncertainty. Following a Great Recession, student enrollment in private schools dropped by around 40 percent within the hardest-hit metropolitan areas. If even 10 % of non-public school students returned to the public system, states' education-funding liabilities would increase by $3.3 billion, EdChoice estimates. In the midst of an economic crisis, policymakers should resist efforts to lessen programs that generally produce higher amounts of student proficiency, stronger educational attainment, and positive competitive impact on other schools in their vicinity-especially when they achieve those results with a smaller amount per-pupil public funding.

Policymakers could even be advised to consider raising funding caps on private-school choice programs to support increased demand. Owing to declining household incomes, an increasing number of families is going to be permitted to participate in these programs. Demand for private schools can also increase because parents have varying perspectives on how so when students should go back to school. A USA Today/Ipsos poll in late May discovered that less than half of parents support students going back to school in the fall even without the a vaccine. Meanwhile, 58 percent of parents indicated they'd support a hybrid in-person and distance-learning approach, and 59 percent said they would consider at-home learning options like online education or home schooling. A poll through the National Parents Union/Echelon Insights found that parents also differ how schools should help students make up for lost learning time: 53 percent of parents support extending the school day, while 63 percent support extending the college year. Increasing use of private-school choice would allow middle- and low-income parents more options when deciding on a college whose approach to reopening aligns using their own preferences.

In the approaching months and years, schools across all sectors will need to assess and address learning gaps, support social-emotional needs, and protect public health. If state funding indeed declines and private-school enrollment drops, public schools will probably have to provide more services to more students with fewer resources. Public education systems will most likely struggle to maintain student outcomes under these circumstances, and lots of students will backslide.

The long-term consequences of this decline aren't difficult to predict. As public schools struggle to meet student needs, dissatisfied families will appear for alternatives. If more private schools serving middle- and low-income students close, those alternatives will narrow. And, if funding for private-school choice programs is cut, access to those alternatives will once again be limited by families' financial means. Unless policymakers think about the needs of private schools alongside those of public schools, the sector could lose enormous ground in providing families with equitable use of choice.

To make sure, resources are finite, and the diversity and depth of needs are profound. But while protecting private-school choice will certainly force tough choices for policymakers today, it'll preserve better selections for students and families in the future.