In October 2021, when Tom Boasberg stepped down as superintendent of Denver Public Schools (DPS) after 10 years at work, he was no doubt frustrated to see his longtime critics rejoice. What likely disappointed him most, though, was that his strongest supporters abandoned him, too.

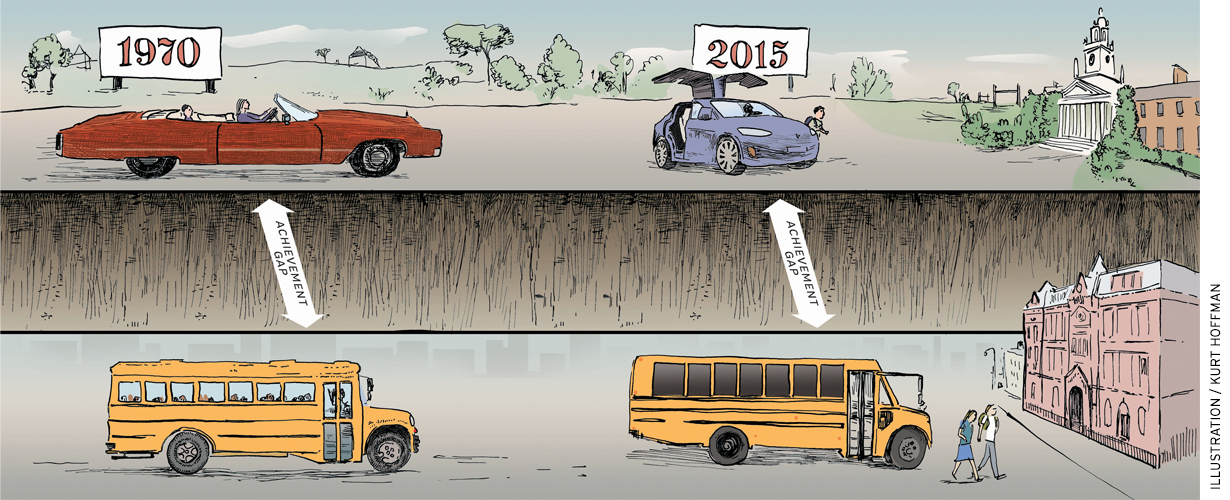

Boasberg's opponents were happy to see him go simply because they think he \”destroyed public education\” in Denver by transforming the 92,000-student district in ways they disdain. Some of his once-strongest supporters lost confidence in his leadership because they don't think he transformed it enough. And everyone seems to blame him for not closing the city's wide and persistent achievement gap between middle-income, largely white students and lower-income and minority students.

Boasberg began his tenure by declaring Colorado's largest district and it is centralized, top-down model for providing public education fundamentally broken. In the years that followed, the superintendent and college board implemented a wide array of unconventional reforms aimed at transforming DPS from the closed school system into a dynamic system of faculties.

When Boasberg first took the reins, it might have seemed wildly improbable that Denver would nearly erase its 25-point lag behind the state in average reading and language-arts proficiency, or the Latino graduation rate would increase by 17 points, or which more than 65 new schools would open. But that is exactly what happened.

In light of those changes, how did Boasberg acquire so many adversaries? The answer is not simple, but a far more seminal question is, how did he manage to gather enough support to effect these radical alterations in the initial place? Boasberg would be a centrist, and that he built a coalition based on pragmatism and a shared belief that change was a long overdue moral imperative. At the height from the national bipartisan consensus on education reform, he was its standard bearer, and, for over anyone before him, he earned his strategy work. His lengthy tenure and also the changes he implemented show traditional school districts and their elected boards can handle reinventing themselves. His work in Denver is really a rebuke to people who insist that traditional districts are the \”one best way\” to supply public education-but it is also a reminder of methods difficult it is to construct an alternative model.

Boasberg first joined DPS in April 2007 as its chief operating officer (COO), hired by then superintendent Michael Bennet, a childhood friend. (Note: Parker Baxter, one of authors of this piece, worked for DPS under both Bennet and Boasberg, from 2008 -11.)

The following month, the Rocky Mountain News painted a dire picture from the district: \”A quarter of the city's school-age children don't attend Denver Public Schools. Among Anglo students, a quarter visit private schools. In some southwest Denver neighborhoods, half the children visit suburban districts. Enrollment at independent charters has skyrocketed 300 percent in six years.\”

District leaders were not angered through the report. Actually, they'd partnered with the reporters to collect and analyze the data. Bennet and also the school board publicly accepted responsibility for the state from the district and issued a phone call for radical change. Located in part around the report, they figured \”operating an urban school district these days based on a century-old configuration will result in failure for too many children.\”

They proceeded to stipulate a vision for any different of district, one which embraced choice and competition and empowered educators and schools by holding them responsible for results. Bennet and the board argued that the district required to \”function a lot more like someone [with educators], building capacity and leadership in the school level and becoming an incubator for innovation.\”

Although Boasberg wasn't yet superintendent once the district published its \”Vision for any 21st Century School District,\” that vision set the path of his tenure.

Boasberg was named superintendent in January 2009, after Bennet was tapped to fill a U.S. Senate seat. Boasberg had played a vital role in developing Bennet's reform plan, and the school board decided to skip a national search.

Aside from Boasberg's 2 yrs as COO of DPS, his only prior education experience was a brief stint as an English teacher in Hong Kong. An attorney by training, and skilled in operations and finance, he had worked on telecommunications policy in the Federal Communications Commission after which being an executive in the private sector. At the time, Boasberg's supporters touted his outsider status as evidence that he would accelerate Bennet's reforms.

Boasberg started by updating the strategic plan launched 5 years earlier. At the time, the Council of the Great City Schools known as the Denver Plan \”one of the very most promising and comprehensive in the nation.\”

Given his private-sector background, it's tempting to see Boasberg as just another \”businessman\” coming in to fix a broken school system. Although he based his reforms partly on private-sector concepts, he demonstrated an in-depth dedication to improving public education in Denver over his decade of service. And unlike some outsiders who attempt to impose business or military discipline on chaotic systems, he took office with an articulated theory of change along with a mandate to implement it. Moreover, Boasberg was targeting transformation, not simply tweaking around the edges. He meant to redesign Denver's traditional city school system from the ground up.

In outlining his vision, Boasberg called around the district to \”acknowledge that our culture historically has not been one consistently based on high expectations, service, empowerment, and responsibility,\” arguing that DPS, like districts nationwide, \”has operated for generations like a monopoly and has suffered from a monopoly's potential to deal with fundamental change, deficiencies in urgency and inflexibility that usually puts the interests of the system and its adults over and above the requirements of our students.\”

The district would still fail its students, he asserted, especially its most vulnerable, unless it had been prepared to recommit to its fundamental purpose-educating students-by reimagining its function and redesigning its structure to satisfy contemporary demands. Boasberg proposed new organizing principles for the district: accountability, empowerment, choice, transparency, and equity.

Over the next decade, these concepts informed the controversial reforms he implemented, including new approaches to school and teacher evaluation, merit pay, and openness to charter and innovation schools (see sidebar). These reforms weren't random. Each was part of a deliberate strategy launched by Bennet and implemented by Boasberg to revamp the city's school district.

The original Denver Plan, introduced by Bennet in 2005, was the very first vision statement in the district's more than 100-year history. Although bold for its time, it had been conventional compared to the revisions Boasberg led 4 years later. In 2010, Boasberg and the board made explicit their intention not just to continue Bennet's controversial reforms but to accelerate them by coupling new organizing principles with a \”theory of action\” to steer the district's work. Boasberg and the board framed the program being an effort to \”fundamentally chang[e] the culture and structure of public education\” in Denver. They praised the progress made under Bennet but were brutal in condemning the district's continued failings. Whether it hoped to make real progress for those students, they argued, the district didn't need only a new thought process, but additionally a new way of acting.

When Boasberg took office, DPS had already implemented a teacher pay-for-performance system called ProComp (Professional Comp plan). Developed in tandem using the teachers union, ProComp had been piloted, supported financially by voters, and was due for renewal when Boasberg became superintendent. At the time, it was one of the nation's first and many comprehensive efforts to evaluate teacher quality and reward strong performance with higher pay.

Although ProComp did not revolutionize the district's relationship with teachers, research has shown it improved teacher satisfaction and retention. It also demonstrated the viability of compensating teachers using an alternative to the traditional step-and-ladder system.

Implementation of ProComp was rocky under Boasberg and is made more complex when the district, in reaction to a state mandate, designed a new and largely separate teacher-evaluation system, Leading Effective Academic Practice (LEAP), which triangulated teacher evaluations according to classroom observations, student academic-growth scores, and student evaluations. LEAP increased flexibility in how teachers were deployed and freed up here we are at strong teachers to support their peers' development; additionally, it expanded teacher-leadership opportunities.

LEAP and ProComp were operated in parallel when, in hindsight, they might happen to be more effective if merged into one system. Later studies show that teachers struggled to know how they could earn more base pay and bonuses under both of these systems. And despite evidence the pay incentives open to teachers under ProComp were built with a significant effect on year-to-year retention, specifically in hard-to-staff positions and schools, Boasberg was never in a position to convince the union of the merits from the system.

Boasberg also focused on other less visible but significant aspects of the district's method of human capital-for example, through his decade-long fight for mutual-consent hiring between school leaders and teachers. For a long time, DPS had frequently involved in \”direct placement\”-the practice of assigning an instructor to a different post, even over the objections of the teacher and principal. Even before he became superintendent, Boasberg zeroed in on the practice as inconsistent having a culture of empowerment and accountability. This year, he partnered with Colorado legislators to prohibit districts from placing teachers into schools without the mutual consent from the teacher and also the principal. Since then, DPS led the state's districts in ending forced placement, also it did so while successfully fighting a lawsuit by the teachers union to maintain the practice.

In 2008 DPS launched its first Call for New Quality Schools, a public invitation for college start-up proposals, whether charter or district-operated. Based on best practices for authorizing charter schools, the procedure developed by Boasberg evaluated applications around the strength from the proposal and also the operator's record of success, without regard to governance type. Charter and innovation schools have raised in number relative to traditional public schools (see Figure 1).

Since launching the annual call for new schools, the district has approved the opening of more than 75 new charter and district schools. Not all have succeeded, and some haven't yet open, owing to lack of space, however, many are now among the district's best performers while serving the highest-need students. The phone call for New Quality Schools fostered the growth of local charter-management organizations, such as DSST Public Schools, STRIVE Prep, Rocky Mountain Prep, and University Prep. Each started with just one school.

Boasberg directed the introduction of something for assessing school quality-both district-operated and charter-and to inform decisions about closing, expanding, and replicating schools. The end result was the college Performance Framework (SPF), a strong model concentrating on student academic growth and achievement and employing multiple measures of performance.

Boasberg and also the school board used the SPF to reshape the district through performance management. Although it is true that he became less prepared to impose consequences on low-performing schools over time, whether in reaction to the larger politics of education reform, resistance from internal stakeholders, pushback from the local community, or the disruption that accountability requires, he nonetheless led radical interventions in a large number of schools.

Using evidence from the SPF, the board intervened in approximately 40 underperforming schools, requiring them to close, restart, or accept replacement by another operator. (As of 2021 -19, the district comprises more than 200 schools. Approximately 150 seem to be district-managed, 50 of which have particular autonomy as Innovation Schools; and 60 schools are district-authorized charters.) DPS hasn't closed or replaced a district-operated school since 2021, and following the most recent board election in November 2021, it suspended its intervention policy. But last year, right before Boasberg left, the board approved a revised policy that requires more community input but maintains the intervention requirement for chronic underperformance.

He argued that \”accountability without autonomy is compulsion\” which real accountability for student outcomes requires giving educators treatments for inputs. In 2008, Boasberg, as COO, caused state legislators to enact the Innovation Schools Act. What the law states allows districts to free some district-operated schools from various rules and policies so they can operate (and innovate) more as charters do, wielding greater autonomy over their time, staff, and cash. DPS has utilized what the law states to create new schools and as a turnaround strategy for troubled ones. According to some observers, Boasberg became more unwilling to relinquish control to varsities with time, especially as the impact of these decisions around the district's central office grew. Still, DPS today has a lot more than 50 innovation schools and three innovation zones, enrolling one fourth from the district's students.

Boasberg certainly did not end inequity in Denver's schools, however the changes he implemented appear to have produced real improvements for the district's diverse students.

Rightly or wrongly, superintendents get much of the credit or blame for district performance. Upon Boasberg's departure, DPS touted improvements under his leadership, including enrollment growth, improved graduation rates, a reversal from worst to first in student academic growth among major Colorado districts, a tripling of Advanced Placement activity, a dramatically reduced drop-out rate, and the opening of more than 65 new schools alongside turnaround or closure in excess of 30 others. Boasberg himself has cited the growing numbers of Latino and black graduates being an especially meaningful accomplishment. Despite these measurable gains, his critics remain unconvinced of his success.

Was the development in DPS enrollment purely a byproduct of Denver's rapidly growing population? Some evidence suggests otherwise. In a state that embraces school choice, the marketplace provides some clues regarding changing demand. Because the 2008 -09 school year, the amount of students choosing to attend DPS from another district is continuing to grow quicker than students opting out of DPS schools-though more students still choose other districts every year than decide to attend DPS schools from elsewhere. In terms of students opting from the public system altogether, the number of children attending private schools located within DPS boundaries fell by more than 30 percent between 2009 and 2021, when compared with merely a 9.4 percent decline statewide (see Figure 2).

Measures of improvement in student performance must be evaluated considering any changes towards the district's student composition over Boasberg's tenure. Despite a remarkable DPS enrollment gain of more than 17,000 students, measures of racial, ethnic, and economic diversity are little changed. In 2021, as in 2009, a majority of DPS students were members of minority groups, though there has been a slight increase in white students (see Figure 3a). The share of Denver Public Schools students receiving free or reduced-price lunches has always been stable, while the share of English learners has increased slightly (see Figure 3b).

DPS experienced substantial improvement within the four-year graduation rate since the 2009 -10 school year, when a new formula for graduation rates was adopted (see Figure 4). Latino students registered the greatest gains. The progress in graduation rates is mirrored by a declining drop-out rate. And lastly, remediation rates-proxies for how prepared graduates are for higher education-also fell during Boasberg's term, while the immediate college-going rate rose.

Improvements in the district's academic performance were already happening when Boasberg took the helm of DPS. Outside observers noted that between 2005 and 2010, DPS moved from worst in median student academic growth to join the top large districts in Colorado in achievement. Under Boasberg, the district has experienced faster-than-average development in student achievement based on the state's growth model but nonetheless lags state levels of proficiency, with worrisome gaps between student subgroups (see Figure 5).

On the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP), the organization A+ Colorado figured DPS students in 2021 performed roughly in the midpoint of huge urban districts nationally, but with more dramatic achievement gaps along socioeconomic lines. Attributing changes in district performance to specific kinds of schools (traditional, innovation, or charter) is challenging. Education Research Strategies reports growth in ELA achievement for all types of DPS schools, but highlights an outsize contribution from charter schools. A+ Colorado found in May 2021 the \”schools using the largest gains in relative performance reveal that a variety of schools and academic programs have demonstrated improvement: from traditional district-run schools, to specialized programs, to charters and innovation schools.\”

Still today, a number of Boasberg's critics, dedicated to the monolithic system he sought to transform, are demanding the district return to its old ways. The teachers union really wants to jettison the district's pay-for-performance system and revert to the traditional step-and-ladder salary scale. Some community groups wish to abandon the common-enrollment system and return to attendance boundaries. The union has called on the district to exchange its multi-measure school performance framework with the state's less rigorous version. And Boasberg's most ardent adversaries don't cherry-pick. They oppose all the changes.

Why, though, do some who originally supported his approach also see his tenure as a failure (or at best absolutely nothing to celebrate)? The answer says a great deal about Boasberg, but it says much more about the state of bipartisan education reform.

When Boasberg became superintendent in 2009, a pro-reform Democrat was at the White House, Boasberg's friend and predecessor was at the U.S. Senate, and Democrats for Education Reform was increasing. His boldest reforms arrived these early years, when his support among fellow reformers was strongest. He could implement radical changes by framing them in terms of which were at once pragmatic and aspirational. Attractive to liberals' feeling of fairness, he confirmed their thought that the system was rigged against the least advantaged. By making transformation from the district a moral imperative-one essential to right a historic and ongoing injustice-Boasberg managed an assorted coalition of support among civic and business leaders, community advocacy groups, and supporters of charter schools and choice. However the trajectory of his impact and influence in Denver tracks neatly using the fate of bipartisan education reform in Washington, D.C., and across the nation. As the shared enthusiasm for standards, accountability, and selection began to fade, so too did Boasberg's shine.

By their own admission, Boasberg is an introvert who lacks the charisma and political skills of his predecessor. Perhaps partly for that reason, he may happen to be more prepared to make decisions that may have ended his political career. This courage earned him a national reputation as a bold reformer and helped him secure the support of numerous advocates who had long attacked the district.

For a period, Boasberg seemed unstoppable. Ironically, he implemented a lot of his most aggressive reforms in the first four years at work as they had the support of only four of the board's seven members. Boasberg eventually gained the support from the entire board whenever a slate of reform-friendly candidates replaced his three detractors in 2021. But by that time cracks had already commenced to emerge in his coalition. With the board's unanimous support, his advocates expected him to maneuver their agenda along more aggressively. When he didn't, he sealed his fate.

In the years that followed, even while Denver continued to rise in national prominence, a lot of Boasberg's leading supporters grew frustrated because it became clear that he was content to allow the district, as you onetime supporter complained, \”coast on its past successes.\”

In 2021, Boasberg lost the unanimous support of the board when two opponents of his reforms won seats. Additionally that year, he a break down major setback when education and civil-rights advocates succeeded in pressuring the district to revise its controversial school-rating system after acknowledging the inclusion of measures advocates said masked low performance. Looking back, that debacle might have caused the final crack in Boasberg's fragile coalition. To opponents and supporters alike, it was proof that the district couldn't be trusted.

In the end, even his strongest stalwarts turned against him. Theresa Pe