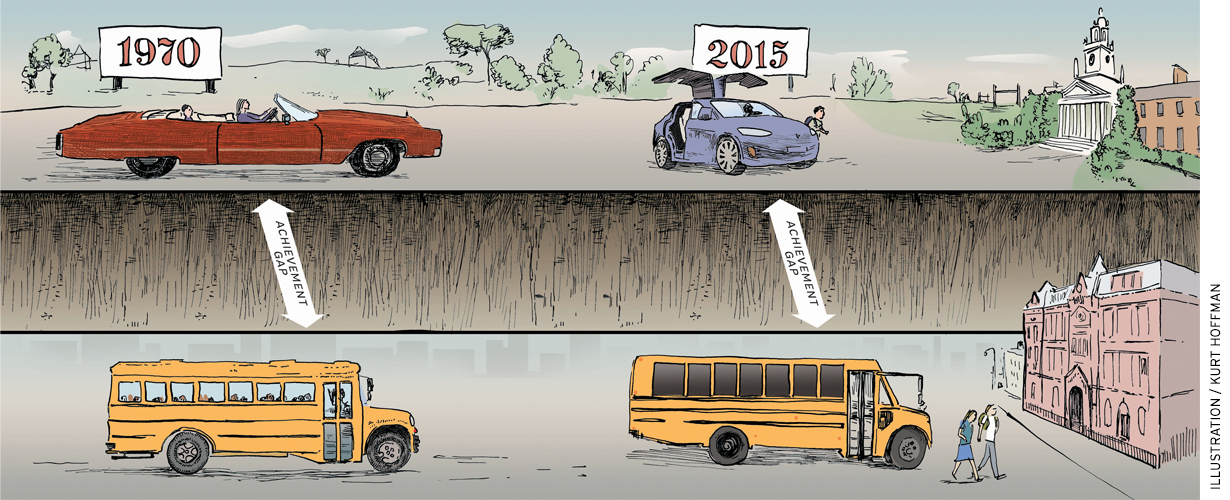

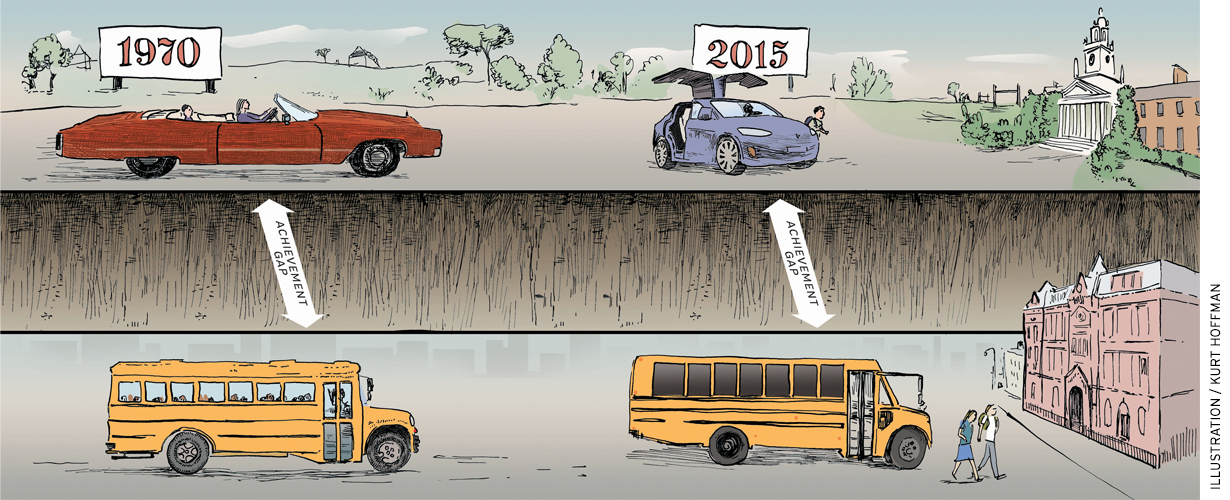

Income inequality has soared in the usa over the past half century. Has educational inequality increased alongside, in lockstep?

Of course, say public intellectuals from over the political spectrum. As Richard Rothstein from the liberal Economic Policy Institute puts it: \”Incomes have grown to be more unequally distributed in the United States in the last generation, and this inequality contributes to the academic achievement gap.\” Harvard political scientist Robert Putnam, citing research by Stanford sociologist Sean Reardon, says, \”Rich Americans and poor Americans live, learning, and raising children in increasingly separate and unequal worlds.\” Another well-known political scientist, Charles Murray, argues that \”the Usa is tied to a large and growing lower class that's able to care for itself only sporadically and inconsistently. . . . The brand new upper class has continued to prosper because the dollar worth of the talents they convey towards the economy has continued to grow.\”

These analysts have valid reason to express concern. National competitiveness is at stake, as education advocates have argued because the Soviet Sputnik launch inspired the nation's Defense Education Act of 1958. Economic productivity and growth are greater in countries where students perform better in math, reading, and science than in the ones that don't provide their youth exactly the same opportunities to learn (see \”Education and Economic Growth,\” research, Spring 2008). Even though some might see income inequality as the result of life choices about matters for example how hard to work or where you can live, educational inequality seems unfair, because the economic status of the child is away from child's own control. It is an inequality of opportunity that runs counter towards the American dream.

Despite the topic's importance, surprisingly little scholarship has focused on long-term changes in the size of the achievement gap between students from higher minimizing socioeconomic backgrounds. Our new information, presented here, tries to fill this void, using data from four national assessments of student performance administered to representative examples of U.S. students over nearly 50 years.

Contrary to recent perceptions, we find the opportunity gap-that is, the connection between socioeconomic status and achievement-has not grown in the last Half a century. But neither has it closed. Instead, the gap between your haves and have-nots has persisted.

The stubborn endurance of achievement inequalities suggests the need to reconsider policies and practices targeted at shrinking the gap. Although policymakers have repeatedly attempted to break the link between students' learning as well as their socioeconomic background, these interventions so far have been not able to dent the connection between socioeconomic status and achievement. Perhaps it's time to consider alternatives.

Before drawing this conclusion, though, it is important to document the long-term trends within the connection between socioeconomic background and school achievement. Press coverage of the subject typically mentions just the most recent shifts in achievement levels and gaps. Our study broadens the perspective by making full use of nearly 50 years' price of historical data available from four intertemporally linked assessments of achievement in math, reading, and science administered to nationally representative samples of adolescent students born between 1954 and 2001. (By \”intertemporally linked,\” we imply that the test makers in every of those assessments design the tests to be comparable with time by doing items like repeating some of the same questions across different waves.) These testing programs also collect information on students' socioeconomic backgrounds, which we use to create an index of socioeconomic status. We report changes in the gaps in performance between students from more- and less-advantaged backgrounds in the last 50 years.

We discover that the socioeconomic achievement gap among the 1950s birth cohorts is very large-about 1.0 standard deviations between those who work in the very best and bottom deciles from the socioeconomic distribution (the \”90 -10 gap\”) and around 0.8 standard deviations between those who work in the very best and bottom quartiles (the \”75 -25 gap\”). They are very extensive disparities, as 1 standard deviation is around the difference within the average performance of scholars in 4th and 8th grades, or four years' worth of learning. But though these inequalities are large, they've neither increased nor decreased significantly in the last Half a century.

It might be, however, that the picture isn't as dismal as suggested. If overall alterations in society, along with policy initiatives, have proportionately lifted all boats in the same rate, everybody may be better-off, even if gaps haven't significantly changed. Utilizing the same data when it comes to gap analysis, we find gains in average student performance of about 0.5 standard deviations for students at 14, or roughly 0.1 standard deviations per decade. But, surprisingly, over the last quarter century, those gains disappear for students by age 17. Quite simply, there is no rising tide for college students because they leave school for school and careers.

The effects of family background on student achievement are well-documented, but few studies track alterations in the relationship between demographic characteristics and student performance with time. This scarcity of longitudinal analysis partly reflects measurement challenges.

A variety of mechanisms link socioeconomic status to achievement. For example, children becoming an adult in poorer households and communities are at and the higher chances of traumatic stress along with other medical conditions that can affect brain development. College-educated mothers speak more frequently for their infants, use a larger vocabulary using their toddlers, and therefore are more likely to use parenting practices that respect the autonomy of the growing child. Higher-income families get access to more-enriching schooling environments, plus they generally do not face the high rates of violent crime felt by those in extremely impoverished communities. Each one of these along with other childhood or adolescent experiences contribute to profound socioeconomic disparities in academic achievement.

In a second investigation, published this year, Sean Reardon draws on data from 12 surveys which contain info on both student achievement and reports of parental income to estimate gaps in math and reading performance of scholars at the 90th and the 10th percentiles from the household income distribution. As opposed to Hedges and Nowell, he finds that the \”income achievement gaps among children born in 2001 are roughly 75 % larger than the estimated gaps among children born in early 1940s.\” For all those born after 1974, children in families at the median income were falling farther behind those in the 90th percentile, leading Reardon to conclude that \”The 90/50 gap appears to have grown faster compared to 50/10 gap throughout the 1970s and 1980s.\”

Reardon's study and its conclusions happen to be widely cited by both academics as well as in the overall media, and the idea that income-related achievement gaps have dramatically increased is becoming contemporary conventional wisdom. Inside a 2012 article, the New York Times asserts that \”while the achievement gap between white and black students has narrowed significantly over the past few decades, the gap between rich and poor students has grown substantially throughout the same period.\” Another Times piece quotes Reardon as saying, \”The kids of the rich increasingly fare better in class, in accordance with the children from the poor. . . . This has always been true, but is much more true now than 4 decades ago.\”

Differences between your findings reported within the two studies may be because of the focus of Hedges and Nowell on overall correlations between socioeconomic status and achievement, while Reardon discusses disparities between the extremes of the income distribution. They might also reflect the truth that Reardon's analysis utilizes two times as many surveys because the earlier study, including data on newer cohorts.

We, however, explore another possibility-methodological limitations common to both studies. Both estimate trends from data collected by different surveys which are administered to students of varying ages and employ disparate methods of estimating achievement levels and socioeconomic characteristics. As Federal Reserve economist Eric Nielsen points out, when \”data sources have income and achievement measures that do not map easily across surveys, they add an additional layer of complexity and uncertainty to the analysis.\” It is this uncertainty that we seek to mitigate by counting on surveys that provide consistent, intertemporally linked measures of both student achievement and socioeconomic status.

We draw data from four testing programs: two which are part of the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP)-the Long-Term Trend and Main NAEP; the Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS); and the Program for International Student Assessment (PISA). (See sidebar for details.) We include all tests administered to students age 14 or thereabouts and also at age 17. (For convenience, we identify all those tested at ages 13 to 15 as \”14 years of age.\”) All told, we compile observations of feat levels and gaps from 46 tests in math, 40 in reading, and 12 in science, or perhaps a total of 98 intertemporally linked tests over a 47-year period. Across this time span, achievement data are available for 2,737,583 students.

To measure these students' socioeconomic status, we use indicators of parental education and residential possessions as reported by students to create a catalog similar to one designed by PISA. The choice of indicators is determined by the fact that all assessments collect info on family background from students themselves. Young people are thought to be aware of their parents' degree of educational attainment but to possess only an imperfect understanding of their parents' earned income. As a classic study investigating this puts it, income is \”a matter of speculation for many students and therefore inaccurately reported.\” For this reason, the surveys collect economic information by asking students about household items, like the quantity of durable goods and educational items contained in the home. Students are most likely not to have seen their family's tax return. The students, though, are very well conscious of whether they sleep in their own bedroom or share one. Additionally they know whether their home features a dishwasher or a computer. Our analysis thus differs from Reardon's study, which excludes assessments that do not ask students or their parents an immediate question about household income.

We use our constructed index to estimate two disparities for each test: 1) the main difference in achievement between the highest and lowest deciles from the socioeconomic distribution (the 90 -10 gap) and a pair of) the main difference between the highest and lowest quartiles (the 75 -25 gap). We then fit simple quadratic trend lines with these points in order to document how, if at all, the magnitude of these disparities is different with time.

As are visible in Figure 1, the disparities in achievement between students in the highest and lowest socioeconomic status groups are strikingly persistent through the period of time. The socioeconomic achievement divide hardly wavers over this 50 years. In the 1954 birth cohort, the achievement gap between your average of those within the bottom and top deciles from the socioeconomic distribution stood at slightly under 1.2 standard deviations. For those born in 2001, the gap is just slightly less-about 1.05 standard deviations. That's, the most-disadvantaged students have made the same gains in achievement within the decades as those realized by the most-advantaged students.

The disparity between students in the bottom and top quartiles from the socioeconomic distribution was about 0.9 standard deviations for the 1954 birth cohort. This 75 -25 gap falls slightly during the next 2 decades, settling at barely below 0.8 for that cohort born in 2001.

Trends offer a similar experience for math and reading separately. The gap in math achievement, designed for the 90 -10 comparison, shows just a little movement over the period-narrowing in early years but returning to a situation underneath the initial level in recent decades. The 75 -25 math gap narrows slightly with time. In reading, the pattern appears essentially flat for the whole period.

To decide if an alternative way of measuring socioeconomic status yields similar results, we estimate the gap between students who are entitled to the government school-lunch program and people who aren't, as reported around the Main NAEP, the main one assessment that contains these details. The government program provides free lunch to extremely poor students from households below the poverty line, while a reduced-price lunch is available to moderately poor students with a better view incomes (1.85 times the poverty line). The space between the extremely poor students along with other students in the 1982 birth cohort is really a sizable 0.73 standard deviations (Figure 2). When the extremely poor are combined with moderately poor, the gap for this cohort is nearly as large. Over the next Two decades, the space between the extremely poor and students from families above the eligibility line narrows by just 0.02 standard deviations, as the gap between ineligible students and all sorts of those eligible for participation in the program widens by 0.01. In sum, this alternative way of measuring the achievement gap between students from higher and lower socioeconomic backgrounds also shows only minuscule change during the period of yesteryear 2 decades.

Figure 2 also shows the white-black achievement gap. Although this is not accurately thought of as a socioeconomic gap due to the improvements in black incomes, it represents another potential dimension of continuing societal disparities. As Figure 2 shows, there is a sizable shrinking of the racial gap in early period but little change over the latter decades.

Some have hypothesized that the lack of success in diminishing the size of the socioeconomic gap is due to changes in the racial and ethnic composition of the school population. It is true that the ethnic makeup from the school-age population is different dramatically over the past half century, using the share that is white declining from about 75 % to 55 percent. However, these changes do not appear to have materially affected trends in performance gaps. The 90 -10 socioeconomic achievement gap among white students born in 1954 was one standard deviation. Through the center of the period, the divide had declined by about 0.2 standard deviations, but it then rose again by a commensurate amount. Trends for that 75 -25 socioeconomic achievement gap among whites are much exactly the same, confirming that alterations in the ethnic composition of student cohorts do not take into account the unwavering divide between your haves and have-nots.

In sum, our results confirm Reardon's finding of huge gaps in academic performance between students at the extremes of the socioeconomic distribution. The average 90 -10 income achievement gap across the surveys suggested by the Reardon analysis is very similar to the 90 -10 socioeconomic achievement gap we identify. We are, however, unable to replicate Reardon's finding that achievement differentials have risen up to 75 percent over the past 50 years. His results may be a purpose of a addiction to cross-sectional studies that use disparate means of collecting both income and achievement information. Whatever the reason, the trends estimated in his analysis differ markedly from the gaps we observe by using a uniform way of measuring socioeconomic status and data from intertemporally linked surveys administered to students of the same age.

We might feel differently about these persistent achievement gaps when we discovered that all achievement was rising and thus suggesting improved economic futures for those. To put the achievement gaps in context, we describe alterations in the average degree of achievement among students at 14 and age 17 for college students born between 1954 and 2001. Figure 3 shows a substantial upward trend within the average achievement level for all adolescent students of approximately 0.3 standard deviations during the period of yesteryear 50 years, or approximately 0.06 per decade. This trend differs by the chronilogical age of the student, however. Students at age 14 show a general increase of approximately 0.43 standard deviations, or approximately 0.08 per decade, but gains among students at age 17 amount to no more than 0.10 standard deviations, or 0.02 per decade. Further, we have seen no improvement within the performance of older students after the 1970 birth cohort.

Trends in average amounts of achievement do differ in magnitude by subject, however the overall patterns are quite similar. In math, the younger adolescents register average gains of 0.9 standard deviations, while the older ones show a shift upward of just 0.25. At both ages, the reading gains are less. The popularity among younger adolescents amounts to just 0.20 standard deviations over the 50 years and, among older ones, the trend is flat, showing no upward trend whatsoever.

The variations in trend lines for college students at different ages presents a puzzle that we've very difficult answer. Even setting aside the oldest students in our data, we have seen that the average improvement in test performance among 13- and 14-year-olds who take the NAEP tests and also the TIMSS is greater registered by 15-year-olds around the PISA tests. This might reflect variations in test design, or it might suggest that the fade-out in gains begins in early years of senior high school. The lack of an optimistic trend among 17-year-olds for the past quarter century also shows that high schools don't build upon gains achieved earlier, a signal, perhaps, the senior high school has turned into a troubled institution. In any event, there isn't any manifestation of a rising tide that lifts all boats at age 17 when these students 're going into further schooling or in to the labor force.

Importantly, age anomaly that people see within the trends in achievement levels is not based in the performance gaps. Constant social gaps are found across all age ranges.

The achievement gap between haves and have-nots within the U.S. remains as large as it was in 1966, when James Coleman wrote his landmark report and also the nation launched a \”war on poverty\” that made compensatory education its centerpiece. That gap hasn't widened, as some have suggested. But neither has it closed.

The question remains: why has the gap remained consistent? The tempting answer is that nothing significant enough has happened to alter its size. But this would ignore a multitude of factors which have shifted through the years. It is more likely that some changes within families and within schools been employed by to shut the socioeconomic achievement gap while other changes have widened it, with one of these factors largely offsetting one another.

But these negative factors might be offset by other, countervailing demographic changes. Most importantly, differences among children in their parents' degree of educational attainment have narrowed as overall education levels have climbed. So have differences in the amount of siblings in the household. Both factors are essential determinants of student achievement. The total amount of all these 4 elements may well have left the family contribution to the achievement gap at much the same level today because it was for cohorts born in the 1950s.

On the other hand, the caliber of the teaching force-a centrally important factor affecting student achievement-may well have declined over the course of yesteryear several decades. Ladies have greater access to opportunities away from field of teaching. Teachers' performance on standardized tests has slipped, as well as other indicators of selectivity. Teacher salaries have declined relative to those earned by other four-year college-degree holders and therefore are currently low in accordance with comparable workers in other occupations (see \”Do Smarter Teachers Make Smarter Students?\” features, Spring 2021).

These changes affecting the caliber of the teaching force will probably have experienced a disproportionately adverse impact on disadvantaged students. Collective-bargaining agreements and state laws have granted more-experienced teachers seniority rights, leaving disadvantaged students to be taught by less-effective novices.

In short, a growing disparity in teacher quality across the social divide might have counterbalance the impacts of policies made to work in the opposite direction.

Two surprises emerge from this analysis of long-term trends in student-achievement levels and gaps over the socioeconomic distribution. First, gaps in achievement between the haves and have-nots are mainly unchanged in the last half century. Second, steady gains in student achievement in the 8th-grade level haven't translated into gains after senior high school.

Because cognitive skills as measured by standardized achievement exams are a strong predictor of future income and economic well-being, the unwavering achievement gap over the socioeconomic spectrum sends a discouraging signal about the possibilities of improved intergenerational social mobility. Perhaps more disturbing, programs to improve the education of disadvantaged students, while perhaps offsetting a decline in the quality of teachers serving such students, did little to shut achievement gaps. These steadfast disparities suggest the need to reconsider the present direction of national education policy.

Two areas for further exploration seem especially critical. First, scientific study has uniformly discovered that teacher effectiveness is a predominant factor affecting school quality. While there's been ample commentary on teacher recruitment and compensation policies, few programs and policies at scale have directly centered on enhancing teacher quality, designed for disadvantaged students. Second, the achievement gains realized by students at 14 fade by age 17, yet policymakers have left high schools-like the achievement gap itself-in many ways untouched.

We use surveys from four testing programs to research achievement gaps and levels with time. These surveys use consistent style=\”display: block; visibility: hidden;\”>