Facing the typical challenges of urban schooling, including overcrowded schools, mediocre academic outcomes, and dropout rates, the Los Angeles Unified School District has been at the epicenter of big-city education reform over the past decade. District leaders have successively tried new approaches to teacher evaluation, changes in school governance, and initiatives aimed at improving equity for the underserved. And yet, education reform in the Town of Angels demonstrates the complexity and challenge of enacting and sustaining reform inside a highly divided, politically charged urban context. Since the introduction of charter schools in early 1990s, a few major reforms have taken hold. Others have made their splash after which dissipated like puddles within the desert.

The sheer size of the city's sprawling school district, often referred to as a \”behemoth,\” can make it intractable. Greater Los Angeles is home to 13 million people, and the Los Angeles Unified School District rambles across 720 square miles, including 26 cities, with management split into seven board districts and 6 regional offices. Because the second-largest school district in the country, L.A. Unified in 2021 -20 enrolled nearly 420,000 students, with an additional 138,000 students in the region attending charter schools (the highest charter-school enrollment of any school district in the country). The district commands an operating budget of nearly $7.8 billion and spends about $13,000 annually per pupil, similar to the per-pupil expenditure of local charter schools.

Over 75 % of the district's students come from low-income households, and the majority of students are Latinx or Black. Around the National Assessment of Educational Progress, L.A. Unified saw significant increases in average student performance in math and English language arts from 2003 to 2021. Performance slipped in 2021, however (see Figure 1), and the district is constantly on the have a problem with substantial achievement gaps for African American, Latinx, and low-income students.

Key actors around the public-education scene fall into opposing camps, traditionalists and reformers, with both sides boasting broad political power and backing. School board positions, highly coveted, carry a yearly salary of $125,000 for members with no outside employment, in contrast to most school boards across the country, whose members are typically unpaid volunteers. (In the large cities which do compensate board members, annual salaries are usually well below $50,000.) L.A.'s 2021 school-board election had become the most expensive such campaign in U.S. history, with unions and charter-school supporters spending nearly $15 million to back candidates for 2 open seats. Significant outside purchase of the campaign illustrated the trend toward the \”nationalization\” of faculty board elections across the nation.

From 1980 to 2000, L.A. Unified saw substantial enrollment growth that led to school overcrowding. To deal with this case, the city floated several bond measures from 1997 -2005, which voters passed and which resulted in the making of 131 new school campuses.

Recent conditions have now brought the city's education system to a point of peril. The L.A. County birthrate has declined 15 percent since 2010. This drop, combined with the heightened living costs in the city and increased enrollment in independent charter schools over this era, has led to a 20 percent decline in student enrollment within the district schools in the same time period (see Figure 2). Compounding these challenges are state policy changes that now require school districts to improve their contributions towards the state teacher-retirement system. L.A. Unified leaders have forecast a budgetary shortfall of $500 million by 2021 -21. Further, the district risks county takeover of their finances whether it fails to maintain a reserve to meet its contract requirements.

In 2021, 32,000 L.A. Unified teachers and staff, joined by teachers from some charter schools, involved in a six-day strike-the first such walkout within the district in 30 years-demanding higher pay, lower class sizes, more support personnel, and limits on charter growth. Similar to the city itself, Los Angeles's educational product is built upon a divided, shaky foundation, and the potential for a tectonic shift looms.

A consider the past Ten years of reform strategies in Los Angeles, and just how education leaders enacted, implemented, and modified on them time, provides potential lessons for future efforts. Particularly, three fault lines, or illustrative cases, highlight the divisions, coalitions, obstacles, and progress that characterize the decade's reforms: the portfolio management model; multiple-measure educator evaluation; and efforts to promote equity. Together, these three examples illustrate the dynamics of change efforts amid a background of fiscal exigency and fiercely competing constituencies.

At least 18 major cities are presently deploying the portfolio management model, a governance reform intended to spur innovation and improvement. Under this model, the school district allows a diverse set of service providers to operate schools. District leaders take notice of the performance of various educational approaches and employ the things they learn to inform decisions about school models and operators. Districts undertake a new role as \”performance optimizer,\” periodically removing the lowest-performing providers, as gauged by student outcomes, and expanding the operations of more-successful providers. The model engages the college district in building quality by growing and pruning the portfolio. This sort of \”managed school choice,\” advocates say, allows families to choose a college that fits their students' needs and interests while also giving educators the autonomy to innovate.

In L.A., 2 decades of reform measures moved the district toward the portfolio model. From the 1990s and recurring in to the next decade, magnet schools greatly expanded and many semiautonomous school models arose, including site-based management, pilot schools, and \”network partners.\” The new models grant flexibility from particular elements of district policy or even the collective bargaining agreement with the teachers union, or both. For instance, modeled after the Boston pilot schools, L.A. Unified's pilot model, using its \”thin\” collective-bargaining agreement, was widely touted like a promising alternative to charter schools. In 2007, the district and also the union, United Teachers La, agreed to this school model, which lifted some restrictions of district policy and the teachers union contract for a restricted group of small schools. These pilot schools constituted a network that allowed families to name their preferred school. The pilot model had broad popular and political support, although the union and others pushed for limits on the number of pilot schools.

Another model, the network partner, arose in 2006 after then mayor Antonio Villaraigosa lost a bid to take over the district. The la Superior Court ruled that such a transfer of authority violated the California constitution. Villaraigosa was permitted to manage a small group of schools and employ a governance arrangement that granted school-level autonomy over some aspects of operations but few provisions of the teachers union contract. In practice, a number of these \”autonomous\” models had limited autonomy.

To more effectively manage this new portfolio of schools, L.A. Unified has repeatedly reorganized its management structure. For instance, this year, then superintendent John Deasy divided the management of schools into regional offices, with one office designed to meet the needs of semiautonomous schools. This reorganization was meant to enhance supports to struggling schools by giving lower principal-to-supervisor ratios by ensuring that supervisors were amply trained within the autonomies granted to various school models. But this reshuffling, like many before it, was short-lived. When Deasy left office in 2021 and Ramón Cortines took over as interim superintendent, he reorganized the \”behemoth\” into six regional districts the following year. In 2021, current superintendent Austin Beutner floated a brand new proposal to once more reorganize school management into local \”families\” of faculties. In response, one stakeholder wrote to the Los Angeles Times, \”As a former teacher and administrator, retired after 35 years with L.A. [Unified], I can only say this latest intend to divide the district into 32 'networks' certainly sounds

like rearranging the deck chairs around the Titanic-again.\”

Meanwhile, charter schools have been taking hold in the city; in 1992, California became the second state in america to enact legislation allowing charters. While many early \”conversion\” charters in La remained affiliated with the district, most (225 of 275) are now independent schools that administer their very own finances and management. Several high-profile charter management organizations arose in La, including Green Dot, which gained national attention in 2008 to take over a chronically low-performing comprehensive high school within the city. With the burgeoning of charter schools and their possibility to contend with traditional schools for students, plus concerns about the accessibility to facilities, California voters passed an initiative in 2000, Proposition 39, which lowered the voting threshold for passing bond measures to support school-facilities improvement. The referendum also provided charter schools use of \”reasonably equivalent\” district facilities. Currently, 100 charters are utilizing L.A. Unified facilities, with most co-locating, or sharing space, with district schools, a scenario which has resulted in tensions and even lawsuits within the equitable distribution of space.

Much of the debate around charter schools in La centers on the contention they pull funding, facilities, and students (particularly more-advantaged students) away from traditional schools, contributing to L.A. Unified's declining enrollment and fiscal problems and raising concerns about equitable access. Other worries include insufficient transparency over who serves on charter-school boards and just what private interests charters might promote. Within an op-ed piece in the Los Angeles Times just fourteen days before the newest teachers union strike, union president Alex Caputo-Pearl wrote, \”This approach, sucked from Wall Street, is called the 'portfolio' model, and it has been criticized to have an adverse effect on student equity and parent inclusion.\”

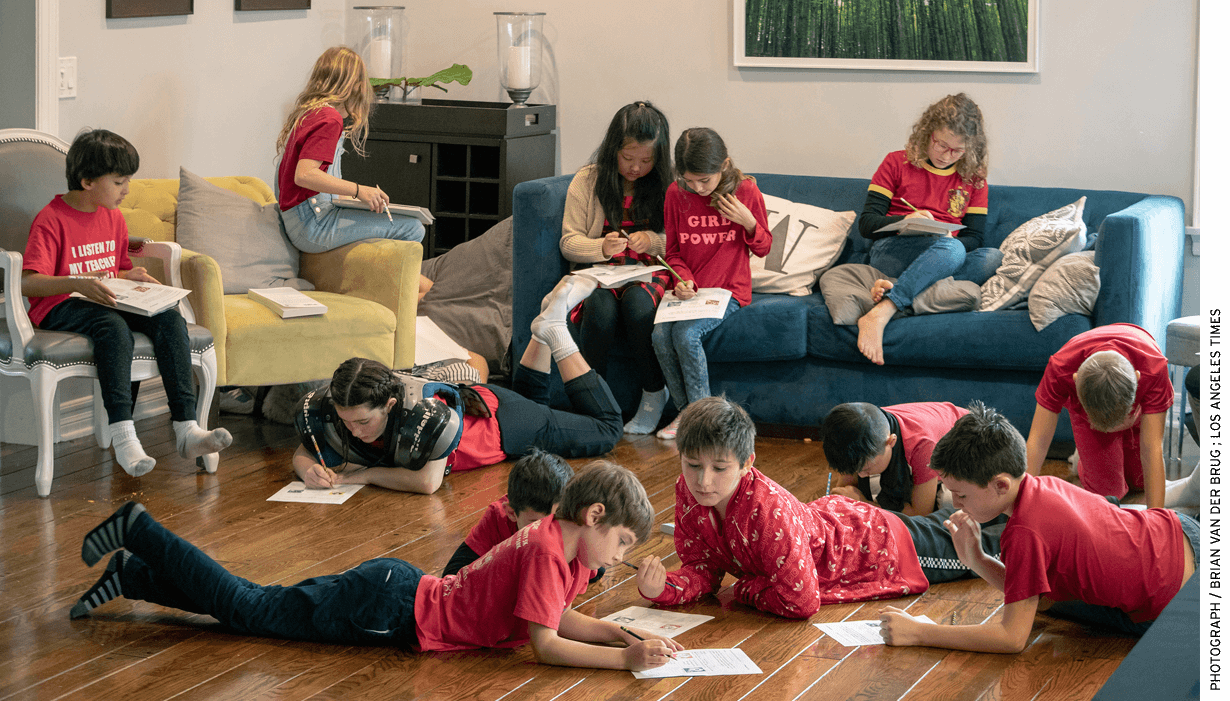

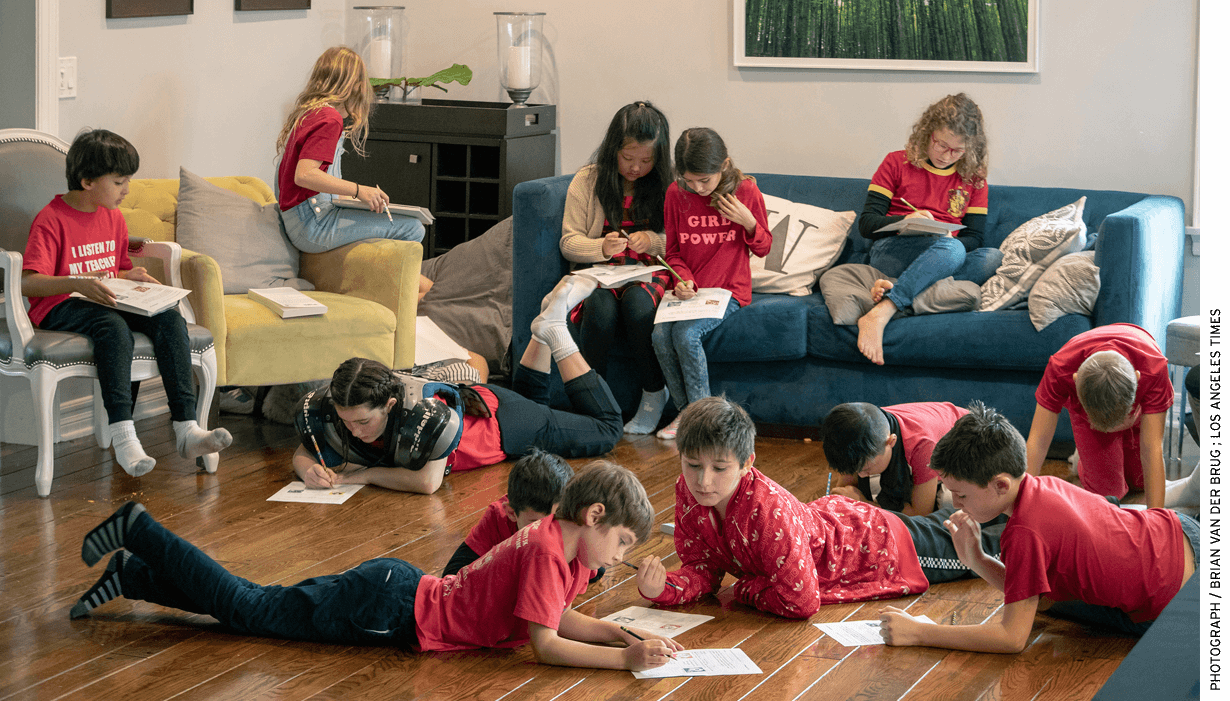

While the share of students enrolled in independent charter schools has certainly increased (to 17 percent in 2021 from 11 percent this year), the overall number of students in traditional schools and independent charters has declined (by 36,441 students within the same period). A shortage of affordable housing in the region and changing demographics and birthrates have contributed to these enrollment changes. L.A.'s portfolio-model schools are divided into two main systems: charters that, while authorized primarily through the school board, operate quite independently; and the district's directly overseen and managed assortment of traditional and semiautonomous schools. Unlike cities with more-unified portfolio models, for example Denver, La has no common enrollment system of these two groups of schools, and fogeys must navigate differing sets of procedures and timelines to enroll their children.

The 2009 Los Angeles Public School Choice Initiative, which formalized a portfolio approach in the district, illustrates the contentious politics of education reform within the city. The insurance policy underwent many substantive modifications through the years due to shifting coalitions and other influences.

Citing the \”chronic academic underperformance\” of numerous district schools and demands from parents and communities for \”a more active role\” in \”shaping and expanding the academic options,\” the school board adopted a Public School Choice resolution in August 2009. Unlike an average choice program to which parents are allowed to choose the school they would like their child to attend, this initiative provided the chance for community members yet others to participate in developing school plans. The resolution invited teams of both external and internal players-such as teachers, administrators, charter operators, and nonprofits-to propose new models for turning round the district's lowest-performing schools (\”focus\” schools) as well as for operating new \”relief\” schools made to ease overcrowding.

Designed for gradual scale-up, Public School Choice involved several annual rounds. In each one, L.A. Unified chose a group of focus and relief schools for participation and then invited proposals to operate them. Applicant teams submitted lengthy plans that covered topics from curriculum to school organization to professional development. Additionally, applicants had to make a choice of a group of governance models that varied in the levels of autonomy schools would enjoy regarding district policies, union contract provisions, and also the use of resources. Models included traditional schools, independent charters, pilot schools (restricted to 20 once the initiative began), along with other semiautonomous internal models. After an extensive review process involving many players, including parents, the L.A. Unified school board selected the operators. In all, 42 schools (14 focus and 28 relief) took part in the first round; 28 (5 focus and 23 relief) within the second round; and 41 (19 focus and 22 relief) in the third round. Through the fourth round of the initiative, all 20 schools were focus schools.

From its start, Public School Choice would be a highly politicized initiative, catalyzing organizing by both union and the charter-school community. In particular, as part of the proposal-review process, parents were invited to \”vote\” for his or her preferred operators and plans. This stage gave rise to electioneering, busing of oldsters to polls, and also the spread of misinformation. In the first year, the demographics of families who voted and attended related meetings didn't seem to match the characteristics from the student population, and the proportion of parents voting was relatively small. After most of the schools in the first cohort adopted the charter-school model, the teachers union increased its efforts to oppose the option initiative, characterizing it as being a \”public school giveaway.\” There were widespread suspicions about the nature of the selection process. The Los Angeles Times joined the public debate in September 2011, opining: \”More than a single management contract was awarded on the basis of political alliances. Charter schools were disappointingly hesitant to undertake the tougher challenge of turning around failing schools; most of their applications were for that new, pretty campuses.\”

Fissures widened as the initiative approached agreed-upon limits on the number of pilot schools that could participate. Because the district entered negotiations with the union over lifting the pilot-school cap, a coalition of community organizations sprang up. The Don't Hold Us Back coalition initiated a campaign in support of lifting the cap and instituting performance-based teacher evaluations. The coalition essentially represented several key interests from the school district, promoting this agenda through full-page newspaper advertisements and meetings with education leaders. The resulting new plan expanded the number of pilot schools and required all Public School Choice schools to operate underneath the collective bargaining agreement, which essentially excluded charter-school operators. But it also made a new semiautonomous school model that allowed any district school to pick from a number of waivers to district policy. While autonomy was limited in key ways, the 550d symbolized a move toward decentralization and represented a big win for the union, assuring additional autonomy for teachers while keeping the union contract provisions. Additionally, it once again returned the district to some divided portfolio, with charter schools operating quite separately from district-managed schools.

Even prior to the board approved the general public School Choice resolution in '09, Mayor Villaraigosa had used his political influence to aid the election of a four-member board majority that favored decentralization and charter expansion. He also joined community members in a rally with the board to pass the resolution. At the start of the implementation from the reform, the union wasn't well organized, but it quickly ramped as much as become a major player. By the last round of competition, the enterprise involved only turnaround campuses, with no charter applicants, before the reform was placed \”on hiatus.\” While the Public School Choice schools remain, the initiative did not continue past 2021.

Amid the turmoil surrounding Public School Choice, the initiative demonstrated mixed results. In turnaround schools, the reform did not produce clear improvements except perhaps in one cohort of faculties, in which the inclusion of enhanced start-up support and the use of \”reconstitution\” (that is, replacement of a minimum of 50 % of teaching staff) appeared to result in student-learning gains. In relief schools, an analysis showed that schools saw unwanted effects on performance in their first year, followed by improved achievement in subsequent years.

In sum, while the portfolio management model, charter expansion, decentralization, and college autonomy are typical reform strategies elsewhere, the political divisions in Los Angeles have hampered the progress of these reforms for the reason that city. Fiscal pressures, limited facilities, and declining enrollment only have compounded these challenges.

Recognizing the critical importance of teacher quality to student learning, districts and states across the nation embraced human-capital reforms previously decade-including efforts to institute fair and accurate teacher evaluations. Spurred by federal policy and incentives underneath the Obama administration, many states and districts allow us \”multiple-measure\” evaluation systems. Typically drawing upon three different measures of teacher effectiveness, scalping strategies try to enhance the quality training by giving educators with clear standards and information about successful classroom practices. The very first evaluation measure often includes at least two classroom observations, performed by a trained evaluator using a detailed rubric. Another measure, called \”value-added modeling,\” uses students' performance trajectories on standardized tests to evaluate a teacher's contribution to student academic performance. This yardstick, while objective, is controversial. Third, scalping strategies often consider other measures of educators' performance, for example teacher effectiveness as gauged by student surveys or contributions to the school outside the classroom. Together, these data in theory inform administrators' decisions on tailored professional development, retention, transfer, and assignment, with the ultimate goal of improving learning and teaching. Some evaluation systems also include incentives, such as bonus pay or promotions to leadership or mentoring roles.

In California, the Stull Act of 1971 (amended in 1999) stipulated that measures of student progress should be part of teacher evaluations, however for decades afterward, L.A.'s teacher-evaluation system lacked teeth: principals observed classroom instruction twice during a teacher's \”on\” year, which occurred every five years for permanent teachers. Evaluators assessed teachers' instruction across several criteria, leading to an overall rating of \”satisfactory\” or \”not satisfactory.\” Under this system, critics noted, ratings were \”widely seen as a rubber stamp, with 95 percent of the district's 33,000 teachers rated as satisfactory. With all of that apparently solid teaching going on, only 56 percent of scholars finish senior high school,\” wrote Hillel Aron in 2011 in LA Weekly.

In 2010, the Los Angeles Times developed its very own approach to value-added analysis and published the ratings of teachers in the district. The Times ratings caused a stir, with critics raising questions about the validity and fairness of this type of evaluation in addition to concerns that publishing the data associated with teachers' names might drag down teacher morale. Indeed, one teacher's suicide was blamed on the general public release of these ratings.

In reaction to concerns over the implementation of Stull evaluations along with a 2009 report from The New Teacher Project calling out L.A. Unified for \”ineffective teacher evaluation and staffing systems,\” the district gone to live in revamp its method of teacher evaluations. Leadership convened a task force of researchers and policymakers to assist develop priorities for reforming the evaluation system along with the district's teacher-retention and development efforts. This year, the district won a $16 million grant in the U.S. Department of Education's Teacher Incentive Fund to support L.A. Unified's planned human-capital reforms, together with a new multiple-measure evaluation system.

Initially, the evaluation system, now called Educator Development and Support: Teachers, included more frequent evaluation for those teachers, composed of two annual classroom observations, plus value-added measurement (calculated differently from the Los Angeles Times measure), student feedback, and assessment from the teacher's contributions to the school community. The machine provided for enhanced professional development tailored to needs identified with the evaluation process. Under the Teacher Incentive Fund grant, the envisioned human capital-reforms also included the creation of a teacher career ladder that involved mentor and master teacher positions with associated stipends in high-needs schools (although these components were never enacted).

On paper, the plan held great promise, but implementation presented serious challenges, even throughout the pilot phase in 2011 -12. The teachers union strongly opposed the program, objecting towards the use of value-added measures along with the proposed four tiers of teacher ratings-including \”highly effective,\” which may actually identify outstanding teachers and thus pave the way for merit pay. The union also objected to the extra demands the evaluation process would put on teachers.

In 2011, annoyed by the district's inability to implement evaluation as planned, parents and students sued the district, superintendent John Deasy, and also the union, demanding a robust teacher-evaluation system that took student progress into consideration, per the Stull Act. The plaintiffs had the backing of EdVoice, a nonprofit funded by philanthropist Eli Broad and others. One former school-board member charged that the superintendent might be \”collusive\” with the plaintiffs, LA Weekly reported in November 2011. Deasy has denied involvement, though he testified during the case, Doe et al. v. Deasy et al., that L.A. Unified did not have a regular process for considering student achievement in teacher evaluations. The Los Angeles Superior Court found the district in violation of the law and ordered it to begin connecting teacher evaluations to student performance in some way, although the court did not prescribe specific policy changes.

This litigation strengthened the case for full implementation from the initial evaluation system, including its value-added metric and 4 tiers of teacher ratings. The union challenged these features with the California Public Employment Relations Board. Still, by 2021, the union and the district returned to the bargaining table. District officials agreed to shorten the evaluation rubric and to use a three-tier rating system. As the union would have preferred the two tiers which were in effect previously, Superintendent Cortines claimed that retaining them means L.A. Unified would lose $171 million in federal funding flexibility under the No Child Left Behind waiver it got as a member of a consortium of California districts. The brand new plan also left supervising principals in charge of teachers' assessments and the way to measure their contributions to student outcomes (that's, progress toward aria-describedby=\”caption-attachment-49692732\” style=\”width: 690px\” >

In January 2021, Los Angeles was rocked by its first teachers union strike in 3 decades. Union teachers across the district and at two independent charter schools took to the picket lines for six days demanding smaller class sizes, more funding for support staff, and higher pay. This strike was two years in the making and represented the culmination of accelerating tensions between the district and also the union-tensions building in the reform experiences described above. The contested issues included charter-school expansion and development of the portfolio model, as well as perceived inadequate human-capital support and funding inequities. Some 98 percent of district teachers voted in favor of the strike, that also drew national support, with well-known leaders from the American Federation of Teachers turning up at the demonstrations. John Rogers of UCLA notes that, increasingly, teacher organizing has included broader issues affecting schools and communities. In L.A., striking teachers sought smaller class sizes, increased nursing and counseling staff, and the establishment more \”community schools,\” in addition to salary hikes. A January 2021 article in The Atlantic described the strike as an example of the long good reputation for student and teacher organizing for school reform in the city, and tied the solidarity of teachers and students to the fact that L.A. Unified employs a significantly higher proportion of Latinx teachers (43 percent) than other urban districts in California.

The context from the strike was complex. L.A. Unified faces a deficit of $500 million in 2021 -21, along with looming insolvency. In part, these financial troubles originate from a change in state policy requiring doubled contribution rates to aid an underfunded retirement system, with the largest increase coming from districts. Saddled with this particular burden and the financial pressures of declining enrollment, L.A. Unified was at an undesirable position to satisfy the union's demands. Ultimately, the union and the district negotiated a 6 percent teacher pay raise, and promised nursing staff at each campus, additional counselors and librarians, and smaller class sizes. In hopes of mitigating these financial pressures, the union, charter proponent and philanthropist Eli Broad, and several businesses backed a measure to enact a new parcel tax-a property tax, usually by means of a set amount, used in California-to support the schools. The measure, which would have needed the support of two thirds of voters to pass, didn't garner a majority.

The negotiations resulted in several symbolic actions, including putting a resolution before the school board to call for Governor Gavin Newsom and also the legislature to enact a cap on charter schools, whose growth the union blames for that district's dwindling enrollment. The board passed this resolution with a vote of 5 to 1. In the state level, an activity force was convened and also the legislature and governor enacted several changes to convey charter law-including some that were intended to limit growth, for example providing district authorizers discretion to deny new charter schools if their creation would harm the finances from the local school district.

These cases-fault lines and ruptures-reveal the initial landscape of education reform in Los Angeles. It's a city with many active political players-including not only the union, the district, and education advocates, but also the media and active local philanthropies. These various players used a number of venues to push their interests, including local board elections, internal policies, state legislation and ballot initiatives, and the courts. There remain stark divisions, in which the interests from the district, unions, charter schools, and community groups are often at odds. Nonetheless, significant reforms have survived within this complex ecology.

One central question remains: why has it been so challenging to implement and sustain education reform in Los Angeles? In this complex landscape, players are continually shifting to succeed often-opposing interests. While many large cities face similar tensions and power struggles, Los Angeles is particularly challenged by its extraordinary size, unremitting financial woes, and leadership churn: the city has had five school superintendents in the past decade alone. With these alterations in leadership came new agendas and alliances, and also the dismantling of prior reforms. The stresses of falling enrollment and deficit funding have heightened tensions around an array of reform efforts. Many see reforms for example charter schools as intensifying the threat to some system where teachers along with other constituencies have a great deal at stake.

Some critics of education reform maintain that reform efforts, particularly charter conversions and selection more generally, often engage in in low-income communities of color and that they privilege other voices and interests over those who work in the city. Some argue as well that such reforms have a tendency to reflect the preferences of philanthropies, often led by white men, who espouse educational and ideological approaches for kids of color, for example promoting strict discipline, that won't reflect the requirements or interests of these communities. Others contend that growing competition one of the city's schools incentivizes these to cherry-pick among prospective students, choosing to enroll individuals with more home supports, higher achievement, fewer special needs, and much less discipline problems. The dimensions and complexity of L.A. Unified and it is policies also disadvantage families with fewer social networks and lower incomes, further exacerbating stratification. For instance, entry into among the district's sought-after magnet programs requires substantial knowledge and time to navigate a complex points-based admissions system. Even when a family seems to steer its way through such systems, limited transportation across this massive city can prevent true choice. While some recent reforms have targeted equity concerns, these matters will need much more attention if the city has any hope of providing all of its communities with access to great schools.

Will the shaky ground of the educational landscape hold, or endure more cracks and fractures? There's both potential and vulnerability in this unstable environment. As new state charter legislation becomes effective so that as enrollment continues to drop, will the number of charter schools within the city decline? What will leaders do to turn around or replace chronically low-performing schools? Public support for that recent teachers union strike and the emboldened advocacy of coalitions fighting for equity may portend deepening political divisions-or hold the possibility for repairing differences and collaborating toward common goals. The following decade of education reform may trust efforts to shore up the stability from the district's leadership and fiscal conditions. The district will definitely need such resources if it is leaders and educators hope to effect changes that will transform the colleges and ultimately help the city's children.